The first Port of Barcelona

The history of the first artificial port of Barcelona

Despite its maritime activity, the port of Barcelona did not actually acquire an artificial wharf until the mid-15th century. Thitherto, it had only had occasional wooden pontoon bridges used as makeshift jetties. In actual fact it did not need one because it already had a natural wharf, Les Tasques.

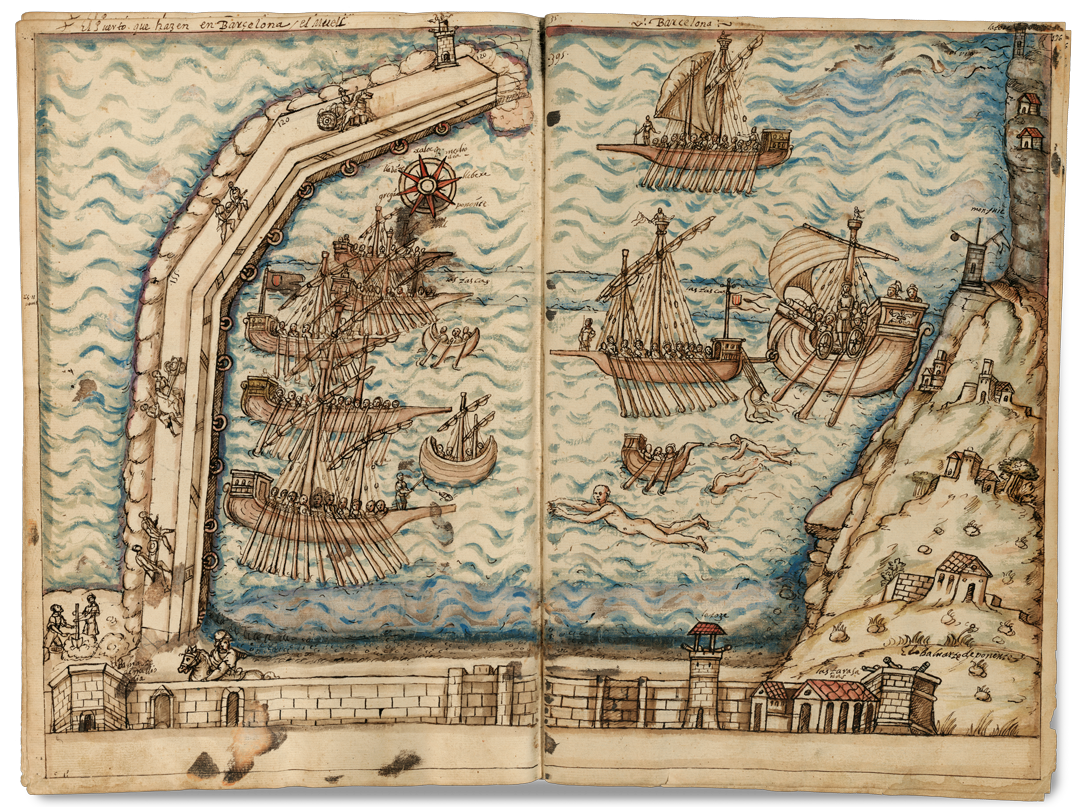

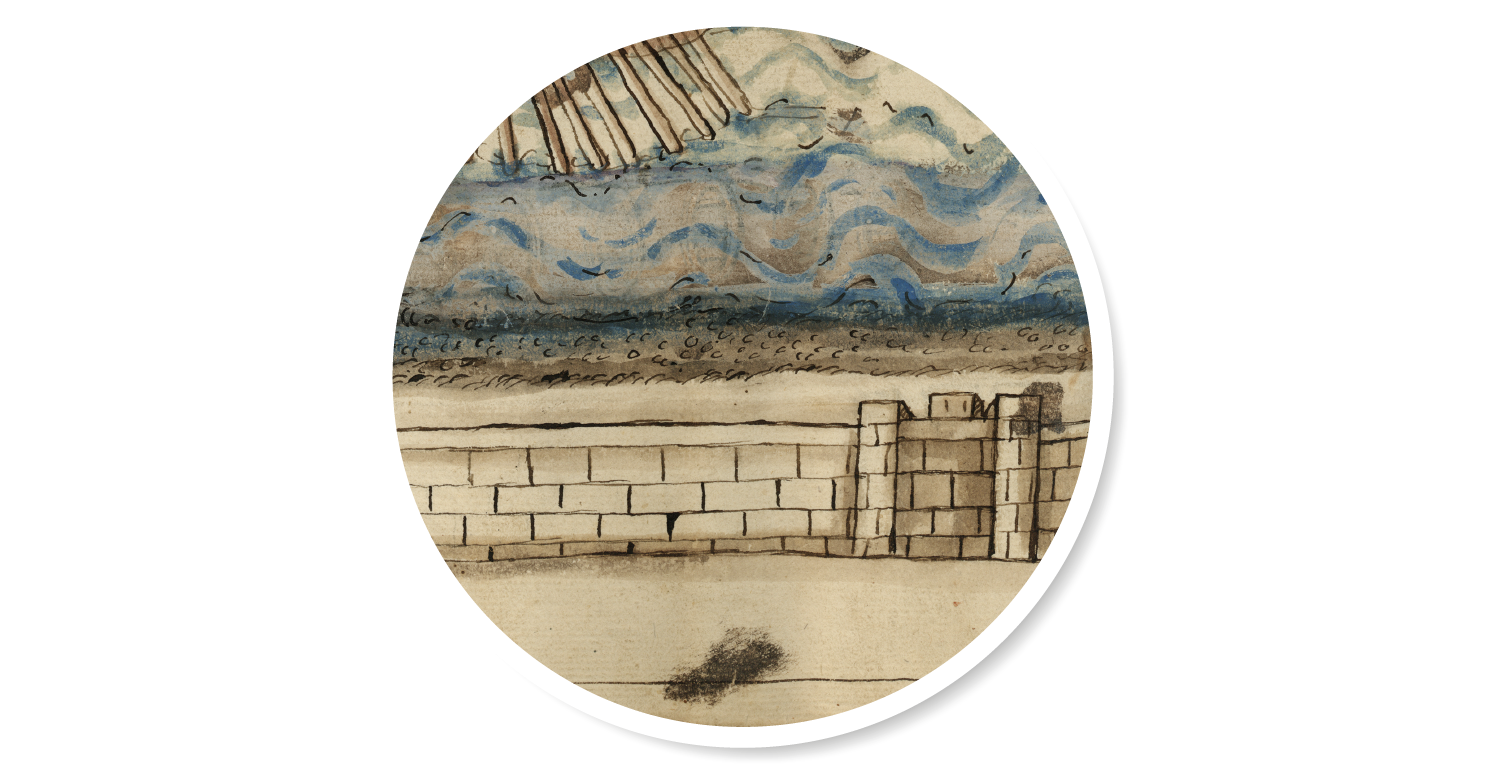

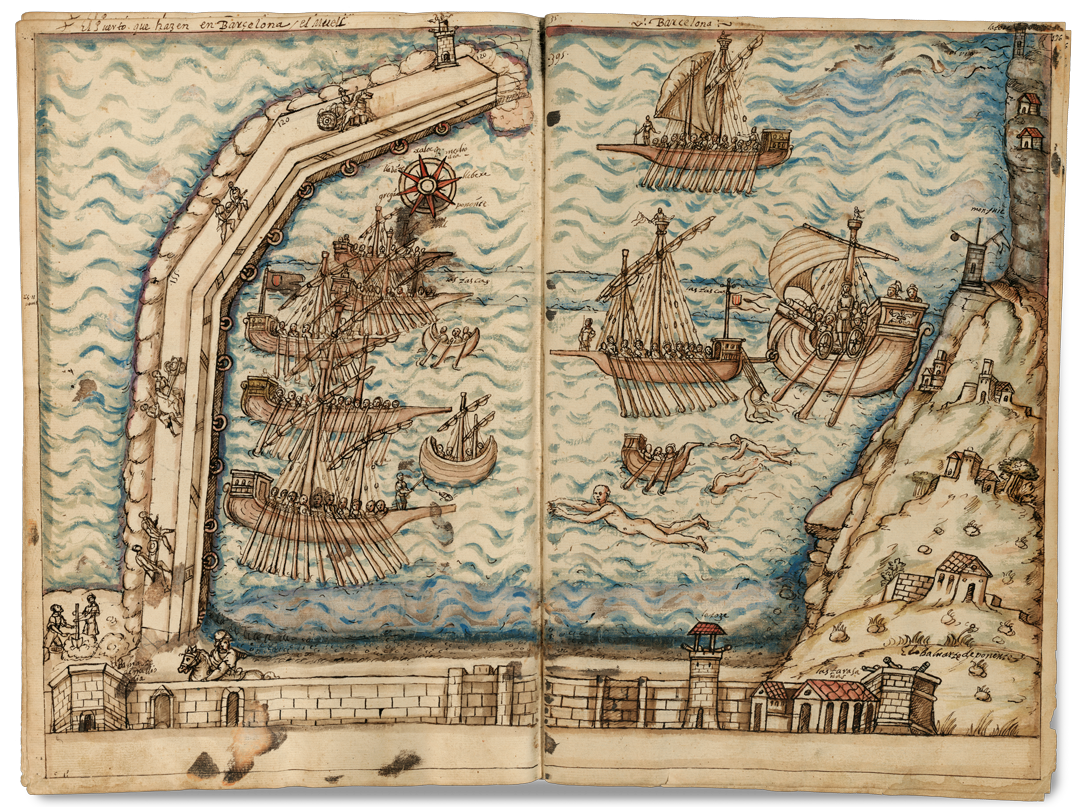

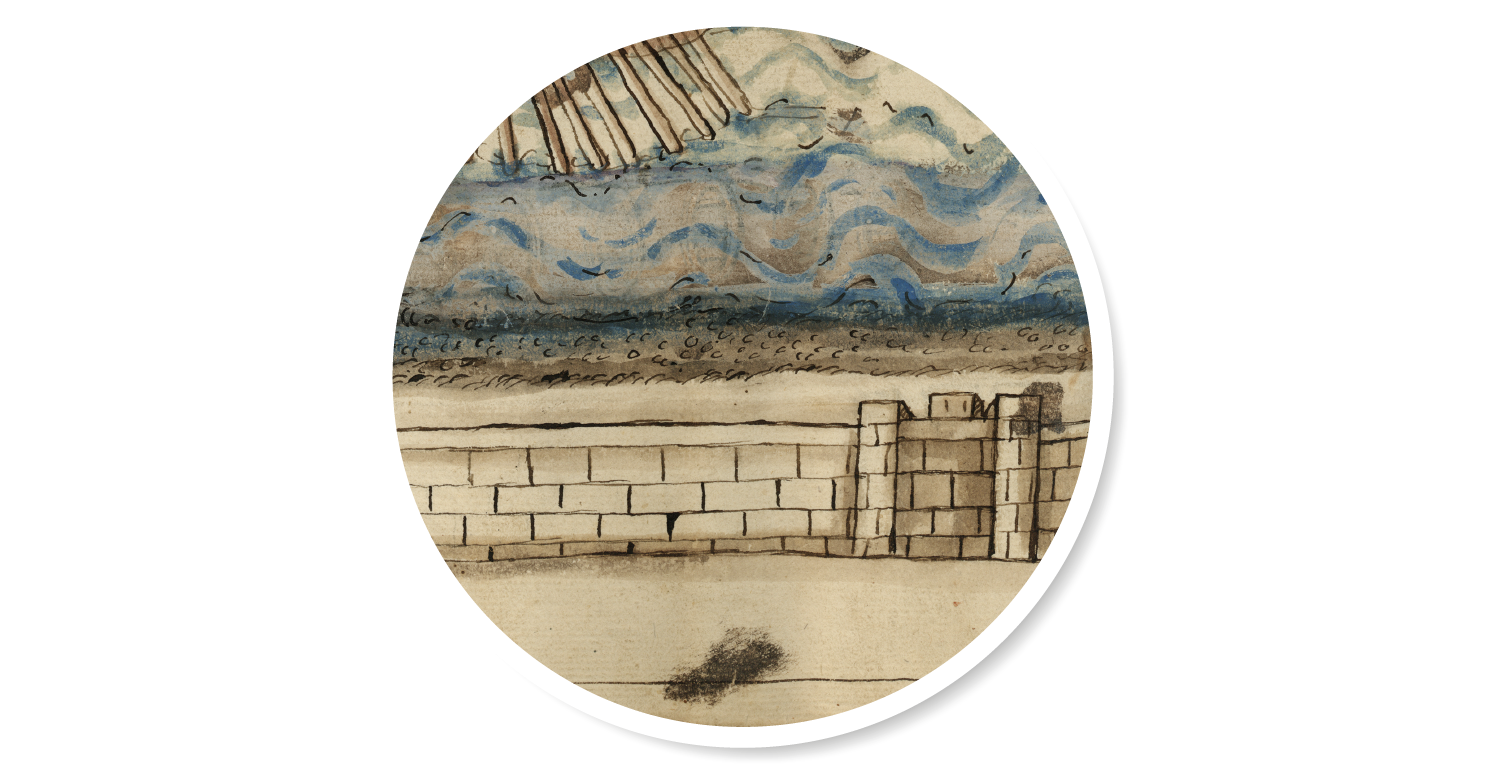

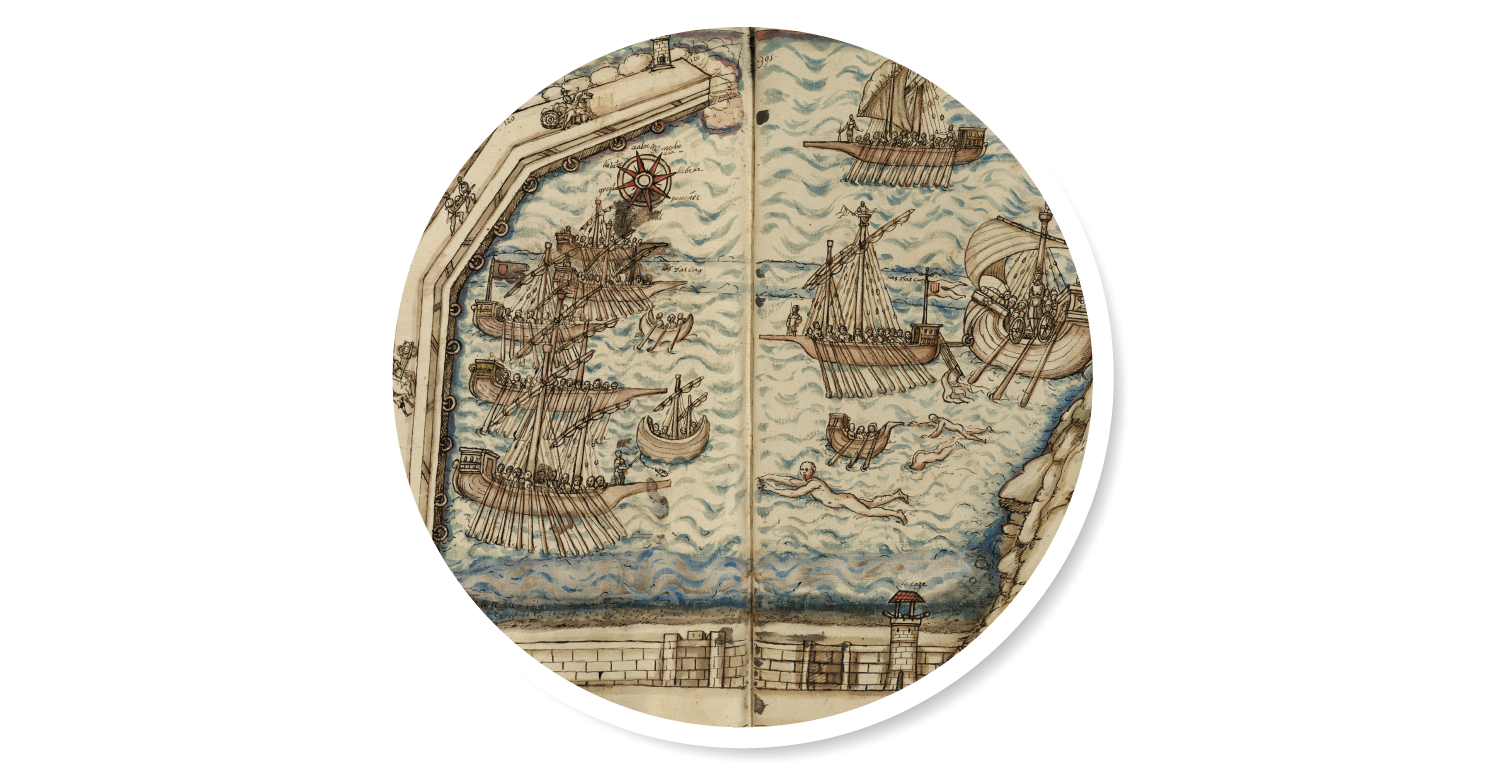

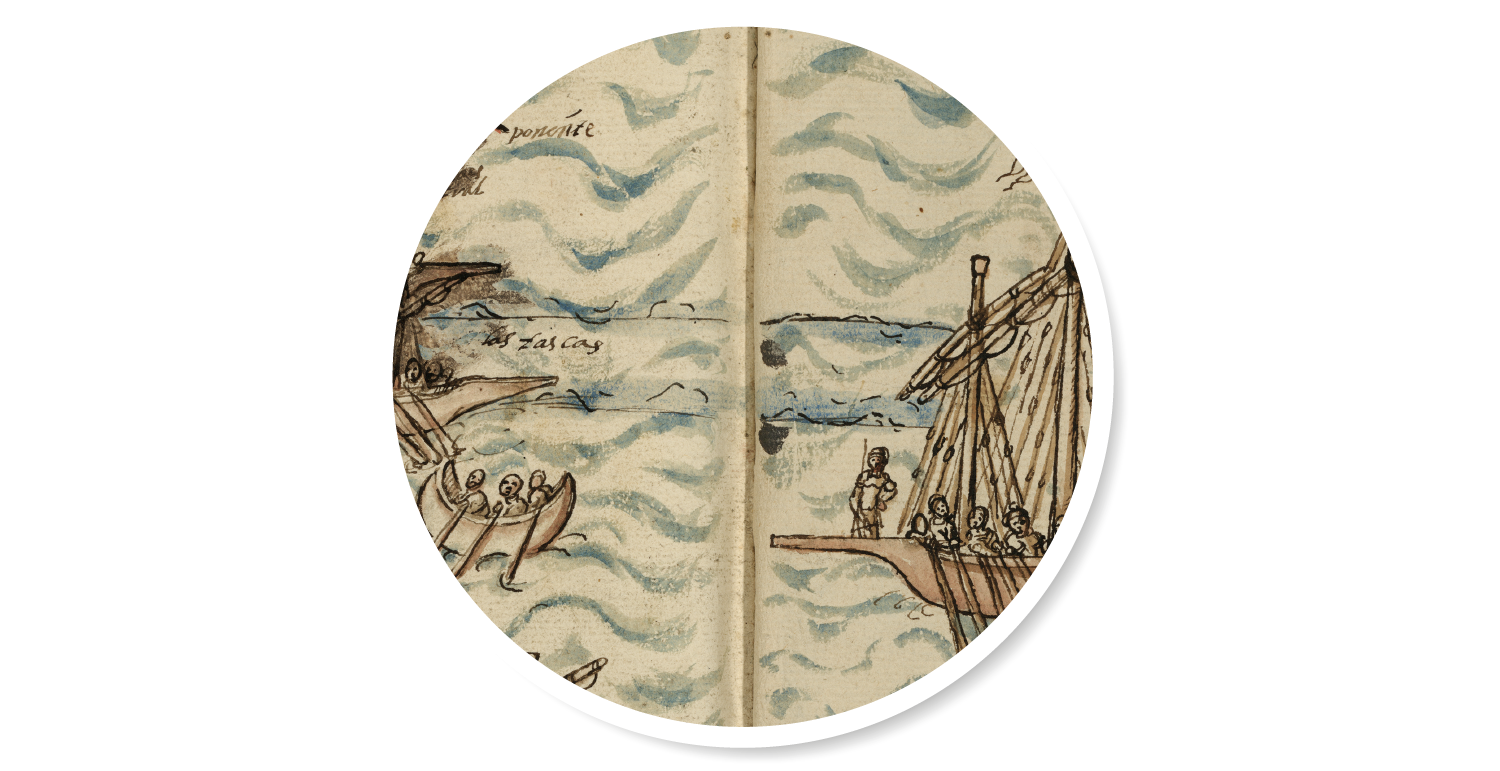

Rafaela Puig drew the first artificial wharf of the port of Barcelona in 1616. BNE

Les Tasques were long stretches of sand that ran parallel to the coast at a distance of about two hundred metres. They harboured a calm and navigable inner lagoon which would eventually hold a port area, all concentrated in what is now known as the Pla de Palau, where goods loading, unloading and trading activities were conducted and sailing vessels were repaired and built.

Taula de Canvi `{`Table of Change`}` - Europe’s first-ever public bank - founded in 1401, brought stability and prosperity, allowing the Council of One Hundred to transform the seafront into a space that symbolised municipal might. Thirty years afterwards, Alfonso the Magnanimous granted the licence needed to build an artificial port, which was paid for through a new tax, the so-called anchorage right. This came in response to the requirements posed by sea trade, which had reached an all-time high.

The decision was taken to consolidate a large part of Les Tasques with a wooden formwork packed with mortar and stone to be able to build a wharf on the eastern side of the city. An east-wind squall in the autumn of 1439 put paid to any progress. Building work was not resumed until 1446. Three pontoons - floating platforms - were assembled to transport stone to Montjuïc, where it was used to build the breakwater.

This initial phase brought the difficulties involved in the project to light. By blocking the flow of the sediments dragged in with the coastal drift, the breakwater gnawed away at the western beach and with it Les Tasques. The huge sandbar that had protected the beach of Barceloneta for centuries began to disappear.

In 1477, after the Catalan Civil War (1462-1472), the project was resumed in the middle of the seafront, following the outline that had been archaeologically documented. The work was overseen by the Sicilian master builder Stacio Alessandrino, who was eventually replaced by the municipal notary public Joan Maians. The project, completed in 1489, extended the breakwater out towards what was left of Les Tasques, which the sea had eroded into a cluster of islets. The island at the end of the wharf was named after the notary public of Barcelona: Maians’ island.

One century later, the Council of One Hundred extended that initial 240-metre-long and 15-metre-wide infrastructure with two 186-metre stretches. That medieval wharf provided the foundations for the modern port.

The continuity of a tradition

The book that recovers the thread of history

After a spell of economic stagnation that set in around the mid-16th century, the dynamism recovered at the beginning of the 18th century was nipped in the bud by the outbreak of the War of Spanish Succession and Catalonia’s ensuing defeat. Towards the end of the century, the enlightened historian, soldier, linguist, maritime economy scholar and politician Antoni de Capmany i Montpalau (Barcelona, 1742 – Cadiz, 1813) wrote his Memorias históricas sobre la marina, comercio y artes de la antigua ciudad de Barcelona [Historical Records on marine, trade and arts of the ancient city of Barcelona], which was published in Madrid in 1779. Capmany’s work heralded a seminal contribution to the economic history of Barcelona and helped to lay the foundations for the creation of the modern port in the second half of the 19th century. The topics that he analysed and recounted in this work are sea warfare and naval power, the merchant navy and trade, as well as the “useful arts” or production sectors of the city.

Historic Map of Barcelona

The cartographic evolution of the seaboard, seafront and port of Barcelona

Epilogue

The Port and the city

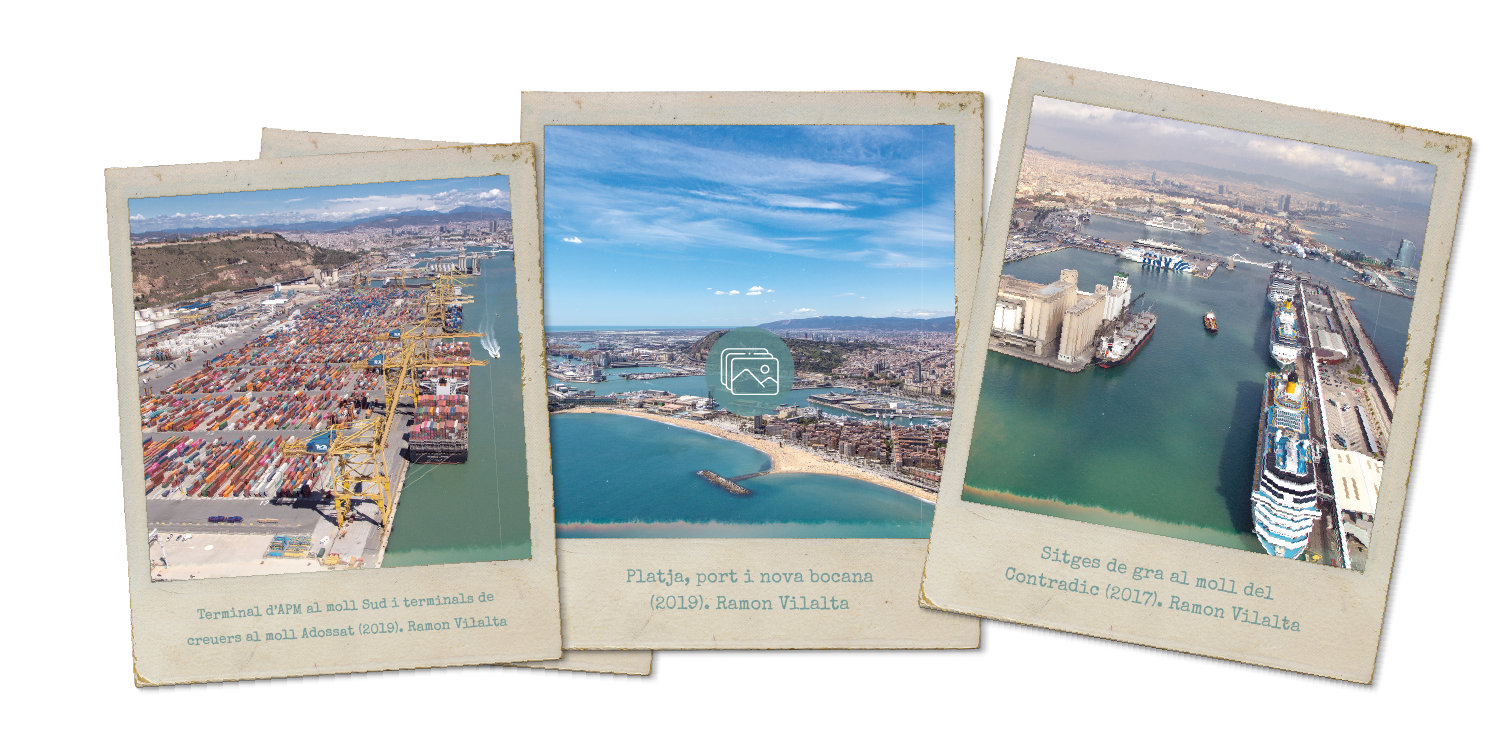

The Historic Map of Barcelona depicts the evolution of the city and its seaboard by dint of the brisk trade and port activity which, halfway through the 15th century, culminated in the creation of Barcelona’s first wharf. Since then, the port has been a key infrastructure and an economic mainstay of Barcelona and Catalonia.

The Barceloneta I attests to and recalls that thriving medieval sea trade. The first wharf originally paved the way for the modern port, the core of the reforms implemented towards the end of the 18th century and, 150 years later, the modern port. A 21st-century port that links us to the world, as it also did more than 600 years ago.

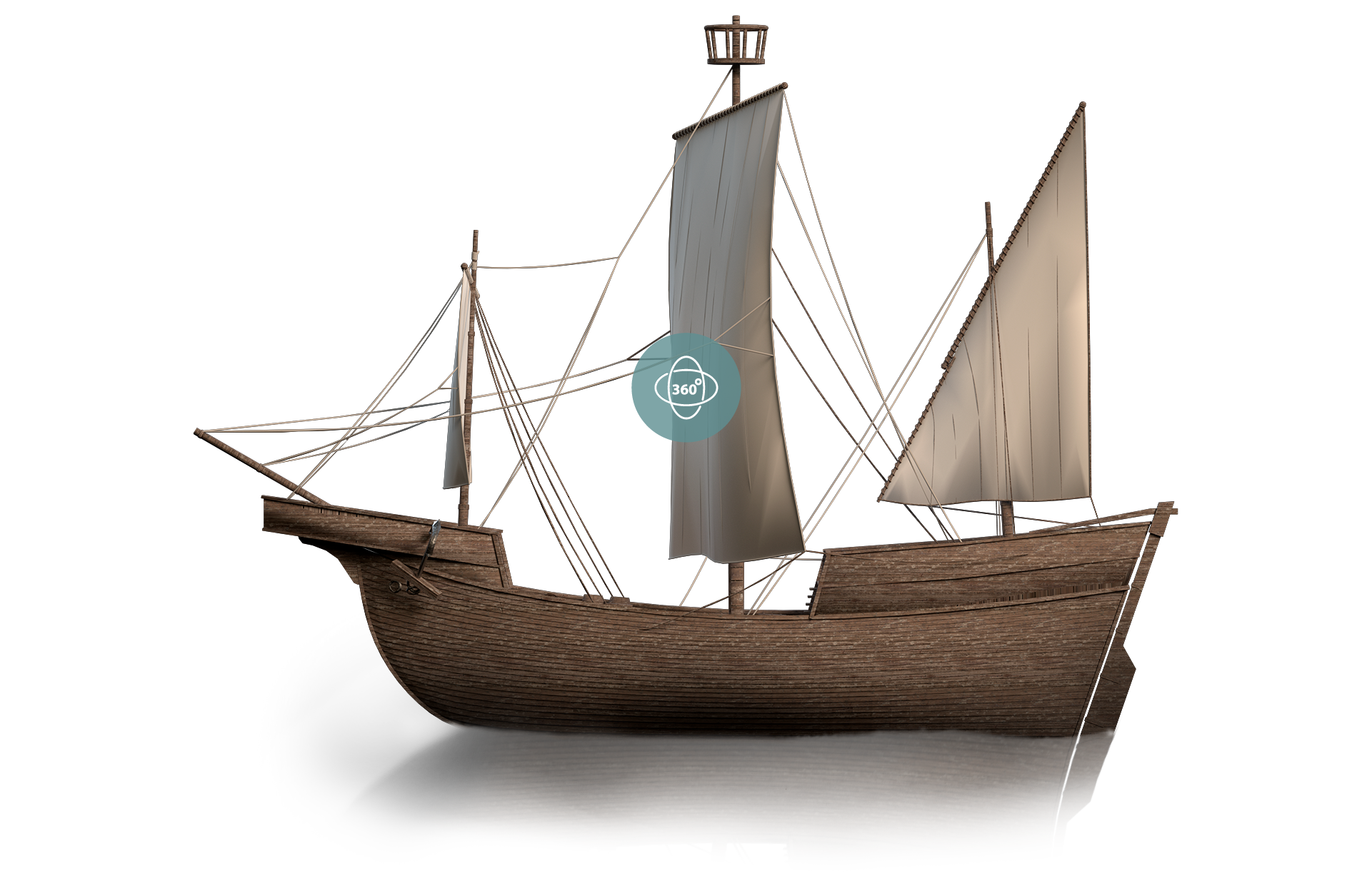

The Barceloneta I ship and the origins of the modern port

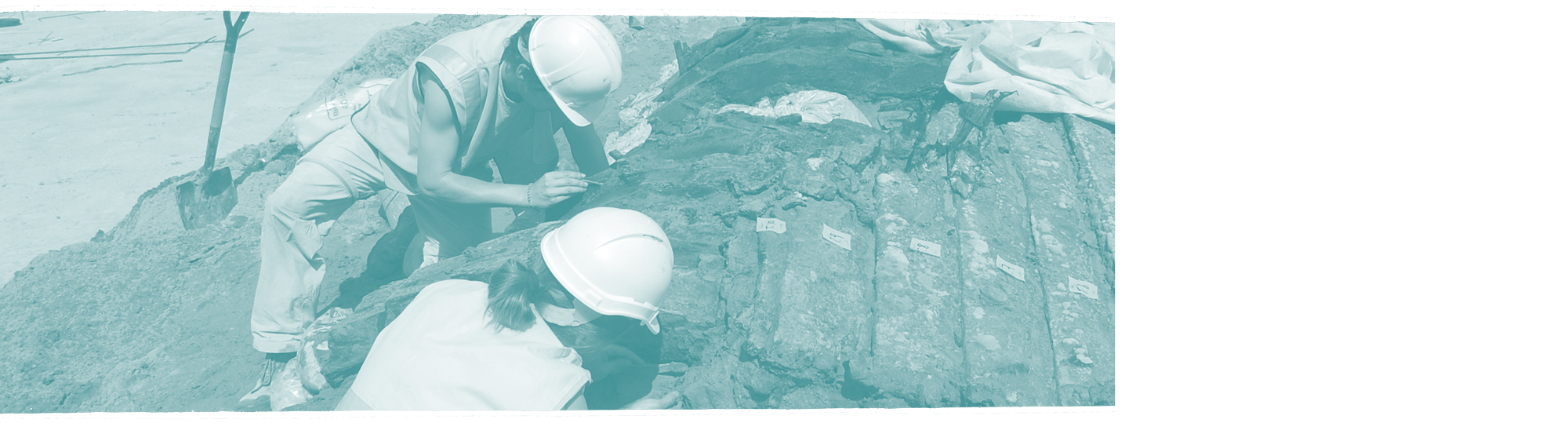

In 2008, the remains of a 15th-century sailing vessel were uncovered next to the Barcelona França railway station at the excavation site of the South bastion of the city's old Sea wall and first artificial wharf. The ship was christened the Barceloneta I. The existence of this vessel, hailing from the Cantabrian coast and probably of Basque origin, in the Barcelona of that period is something of an oddity. No other vessel like it has ever been found elsewhere in the Mediterranean, thereby further heightening Barcelona’s importance as a trading hub since, for more than 400 years, between the 13th and the 16th centuries, the city was one of the key ports in international trade and maritime law in the region.

The Port of Barcelona, in its steadfast commitment to the city’s port-related and maritime heritage, has partnered up with the Museum of History of Barcelona to conserve and exhibit the ship. By dint of this partnership, the Barceloneta I can now be seen in the antechamber of the Palau Reial Major, between the Tinell Room and the chapel of Saint Agatha.

The project has also given birth to this virtual exhibition, which seeks to disseminate the outstanding knowledge gleaned from the archaeological, historic, restoration, conservation and exhibition of the ship and make it available to the general public. The Port of Barcelona realises the importance of the history that shapes us and encourages us to continually seek new horizons.

Conservation of the remains of the Barceloneta I. SAB

Six-masted American schooner for transporting coal (1917) Archive of the Port Authority of Barcelona

Barceloneta I

What could a 15th-century sea vessel be doing next to the França railway station?

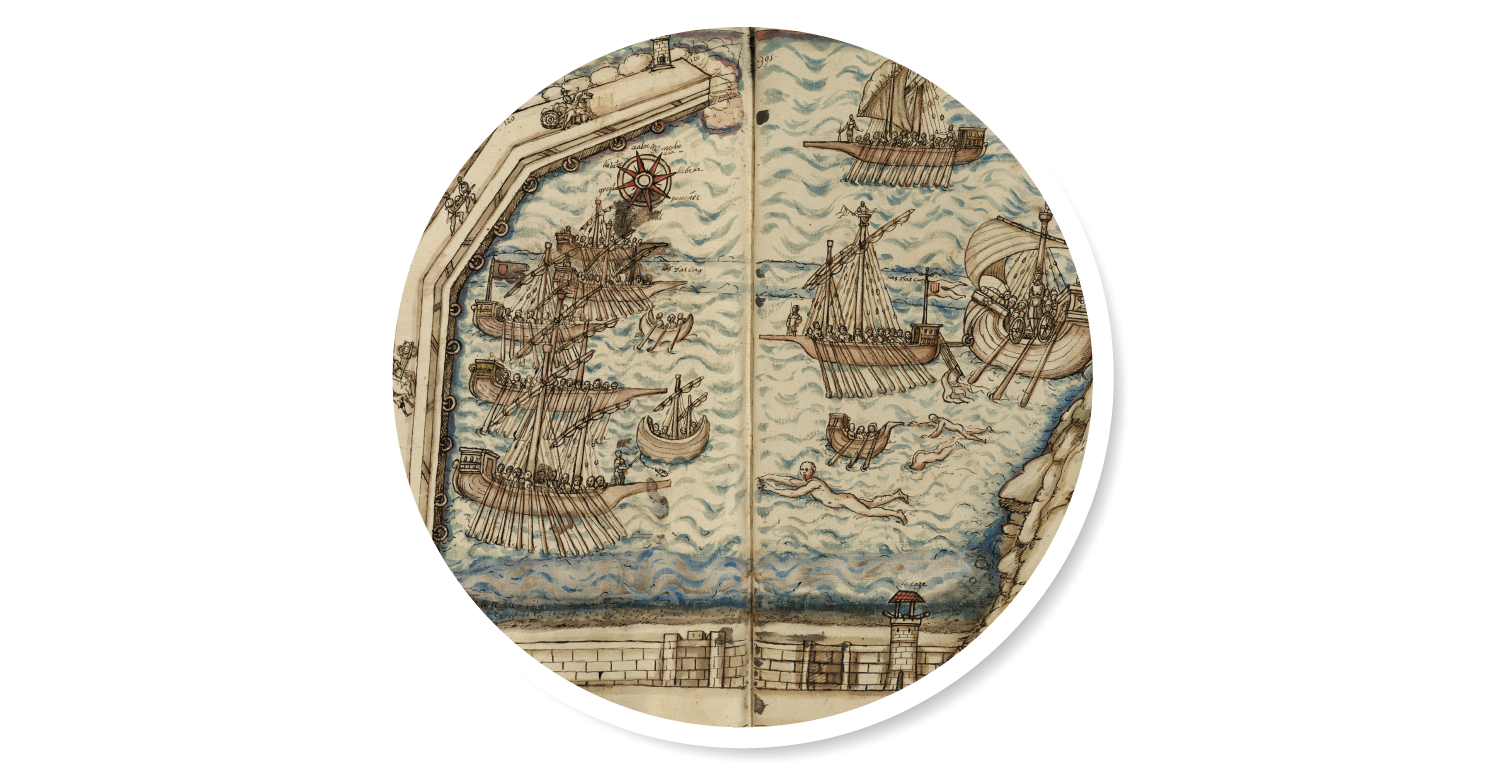

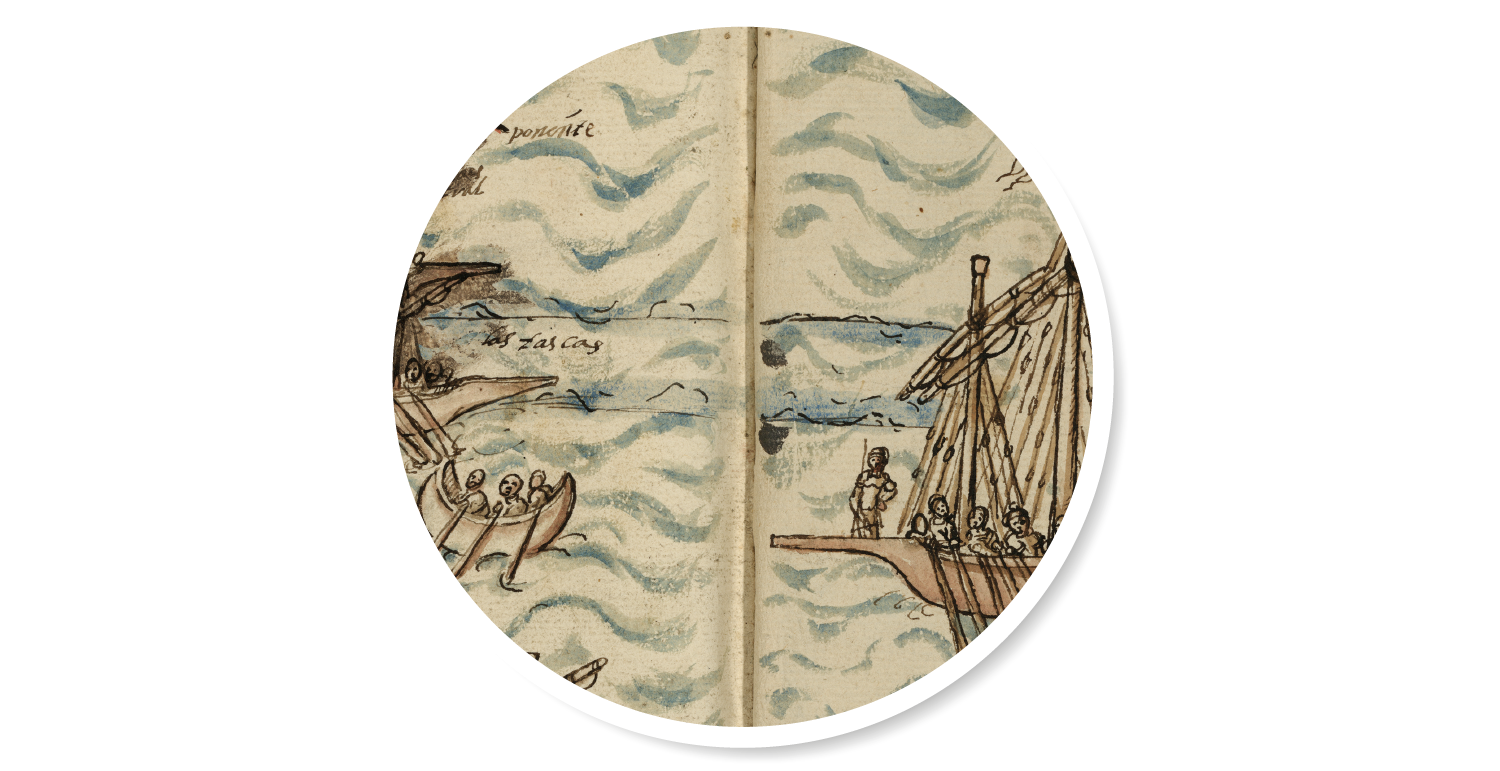

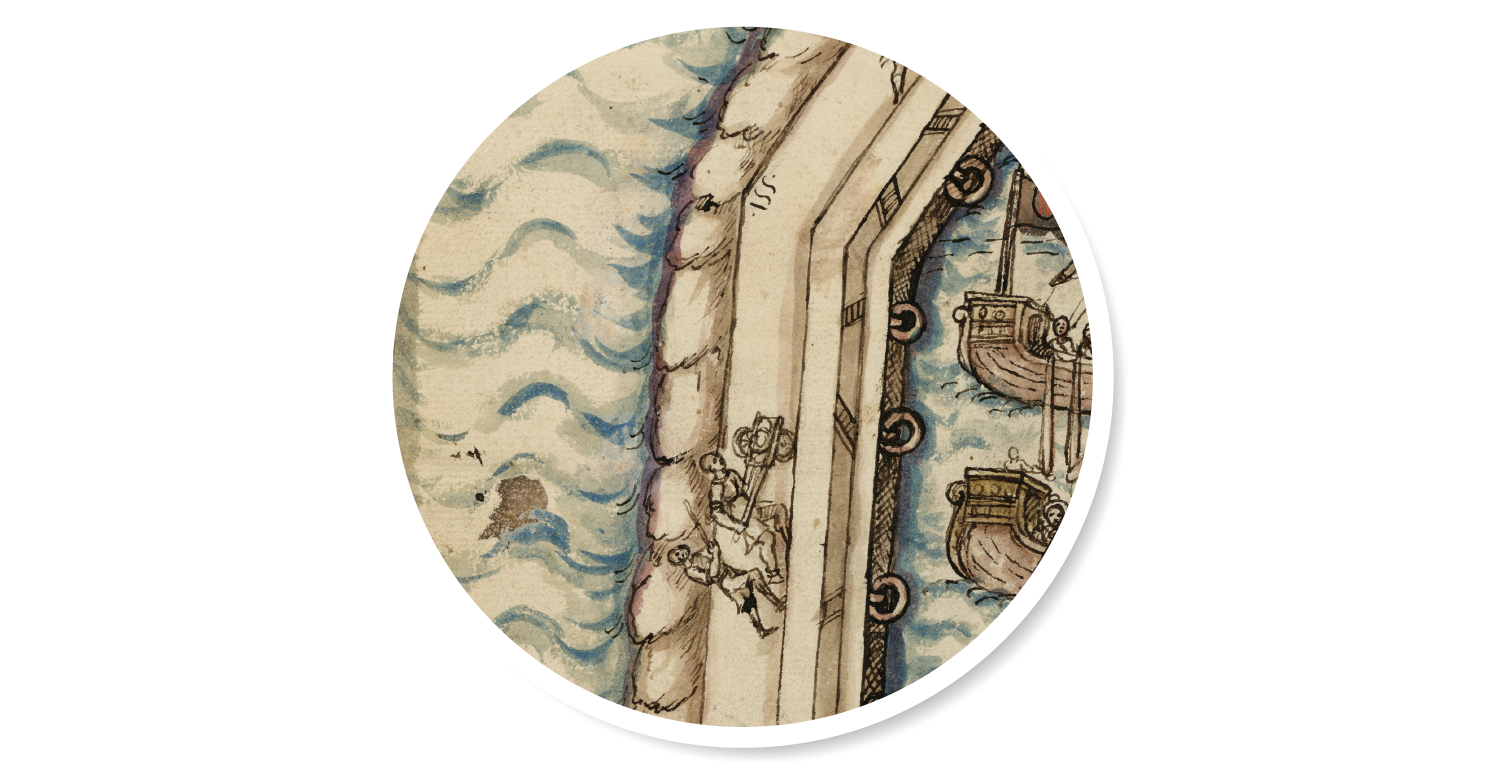

Etching of a view of Barcelona as seen from Montjuïc, published in 1572 in the Civitates Orbis Terrarum book. The original work, dating from 1535, was by Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen, a Dutch painter and tapestry designer in the employ of Emperor Charles V. AHCB

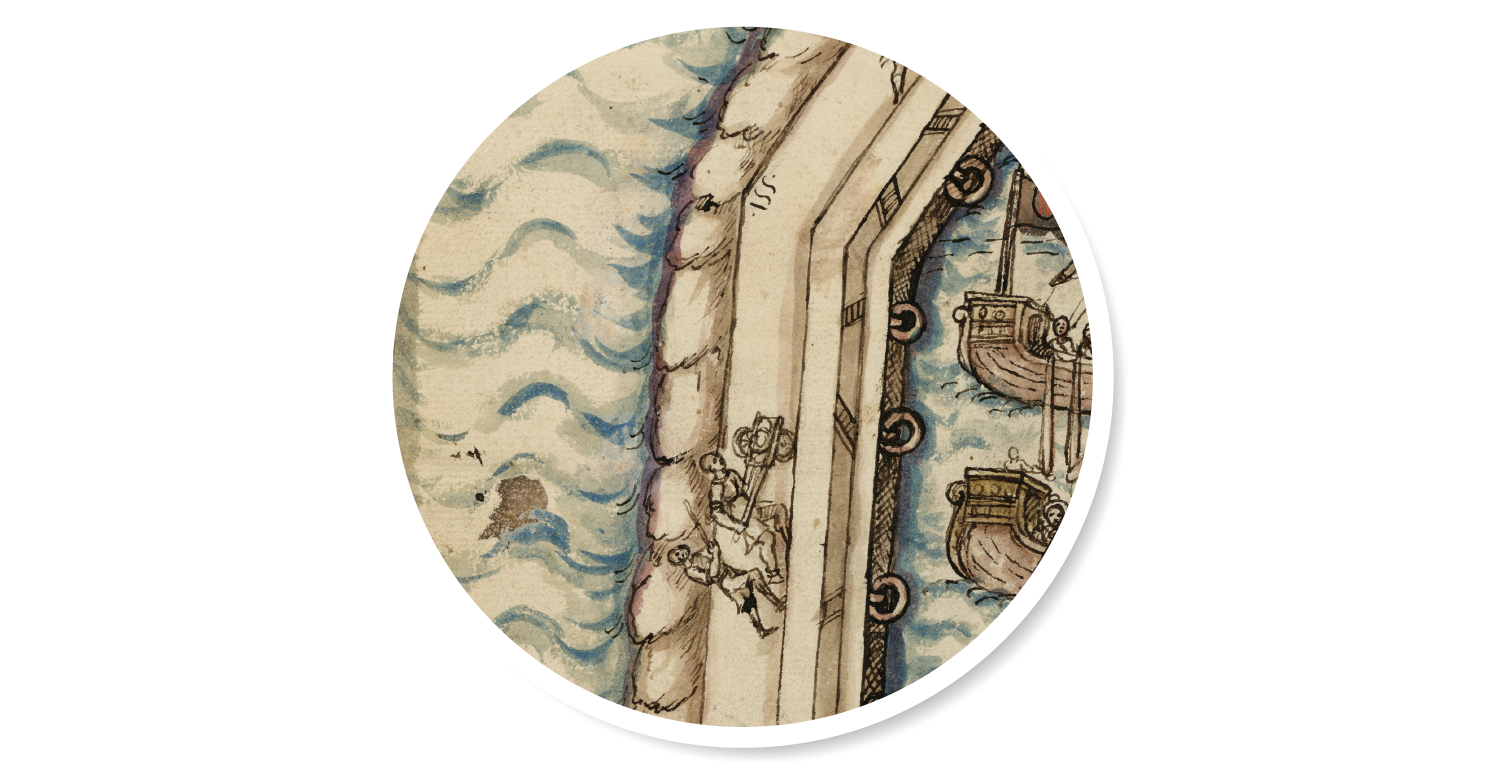

On the right side of the picture of this etching, which dates from 1535, under the rainbow and in front of the seaboard wall, projecting out towards a sea peppered with ships and galleys in formation - perhaps assembled for the expedition to Tunis that same year - the shape of the first wharf of Barcelona, built as of 1477, can be made out. When Jan Cornelisz Vermeyen painted this picture, the wharf already concealed the remains of the vessel which were discovered in May 2008 under the South bastion at the dig site between the França railway station and the Barceloneta district. The ship, dating from the mid-15th century, was christened Barceloneta I.

A bridge of blue sea

The Consulate of the Sea and sea trade in the 15th century

The Catalonian men of the sea were granted privileges to manage sea trade independently, firstly through the Universitat dels Prohoms de Ribera [University of Great Men of Ribera] in 1258 and 20 years later through the Consulate of Traders. The Consulate of the Sea was founded in the mid-14th century and was headquartered in the Llotja, an iconic public building where merchants and traders gathered to do business. Two consuls and a judge represented Catalan trading affairs abroad and dealt with any complaints in accordance with the local adaptation of maritime law that was enforced throughout the Mediterranean. Barcelona was granted Royal privileges to appoint foreign consuls abroad and to oversee the city’s trade expansion directly. By the 15th century, there were already more than 80 such consuls, including those operating out of Majorca.

- Galley

- Vessel

- Boats

- The port breakwater

- Goods warehouse

- Anchored vessels

- The Sea Gate

- The East bastion

- The South bastion

- The West bastion

- Promenade on the wall

- Royal Shipyard

- El Morrot

- The Rec Comtal irrigation channel

- Porxo del Forment and the "La Llotja"

- The church of Santa Maria del Mar

- The convent of Saint Augustine

- Church of Sant Pere de les Puel·les

- The Rambles

- Estudis Generals (Studium Generale)

- Raval district

- The hospital of Santa Creu

- The Church of el Pi

- La Seu (Cathedral)

- El Palau Reial Major (“Grand Royal Palace”)

- The Orchards of Sant Bertran

- The Collserola mountain range

- Pedralbes Monastery

- Sarrià

- Sant Pere Màrtir mountain

- The plain of Barcelona

- The Llobregat valley

- The River Llobregat delta

- El Garraf mountain range

- El Montseny

- The Montjuïc lighthouse

Atop the mountain of Montjuïc, where there is documented evidence of the presence of the oldest human community of Barcelona - from the epipalaeolithic, after the ice age and prior to the development of agriculture - stood a lookout-lighthouse. The tower was tended by a watchman, a sailor by trade, who availed himself of a sail-based and fire system during the day and at night, respectively, to warn the city of any impending peril or threat approaching from the sea. This watchman and his family lived in the house next to the lighthouse. They were connected to the entrance to Barcelona by a path leading to the Santa Madrona gate, a stone’s throw away from the Royal Shipyard. - The Royal Shipyard

The Mediterranean-wide expansion of the House of Barcelona throughout the 14th Century led the city to grow socially and economically as the de facto capital of a maritime empire. Under the patronage of James I, the Royal Shipyard was a major ship-building facility on the sea front nestling in the shadow of Montjuïc. Peter III consolidated the construction of the docks and thus reasserted the naval might of Barcelona and of the Crown of Catalonia and Aragon. The building was extended in the 16th century with a large Gothic room consisting of eight bays protected by a bastion built at the end of the Sea wall. This bastion was connected to the Raval wall. Nowadays, the Royal Shipyard is home to the Maritime Museum of Barcelona. - The Sea wall

In 1285, work commenced on the building of a new wall when the old Roman wall had been all but overrun by new buildings. The new wall was left open to the seafront in order to propitiate sea trade with the city. This opening was eventually occupied by Barcelona’s most dynamic trading venue, the Llotja. The entire wall of the city was consolidated at the beginning of the 16th century, although the Sea wall was not completed until the second half of that same century.

- The port

Following an unsuccessful attempt thwarted by a storm in 1439, work commenced on the building of a breakwater in 1477 and the city gained its first artificial port by the end of the 15th century. The work on the port led to the accumulation of sediments in the area now known as Barceloneta. The Sea wall was closed off in the second half of the 16th century with the building of the East, South and West walls and the Artillery platforms of Sant Francesc and the Wine square. The city’s seafront was further developed through a promenade running along the top of the wall, the top floors of the Porxo del Forment trading building, the new Llotja and the monumental Sea Gate. - Anthonis van den Wijngaerde

A Flemish painter, drawer, draughtsman, surveyor, etcher and publisher (Antwerp, 1525 - Madrid, 1571) who produced this view of Barcelona from the seafront. In 1557, Wijngaerde received a commission from King Philip II of Spain to paint landscapes and views of the main cities of the Crown of Aragon and Castile. He is famous for his drawings of views of cities such as Genoa, Rome, Naples, Madrid or London.

View of the seafront of Barcelona (1563). Anthonis van den Wijngaerde. ÖNB

The seafront (in the second half of the 16th century)

Evening in the city, seen from the sea

In the second half of the 16th century, in the wake of the Catalan Civil War, the shortage of wheat and plague epidemics wreaked havoc in Catalonia and Barcelona. The country’s integration in the Spanish monarchy and the Hapsburg Empire, followed by the absence of the monarchs, the “Castilianisation” of the nobles and Barcelona’s loss of capital city status, engendered a spell of slow decadence. Nevertheless, the capital was an important sea trading port and was the centre of the Mediterranean fleets of Emperor Charles V - particularly following the expedition to Tunis in 1535 - hence its population continued to grow.

The discovery

Excavation work on a car park under a train station uncovered a bastion, a wharf and a ship

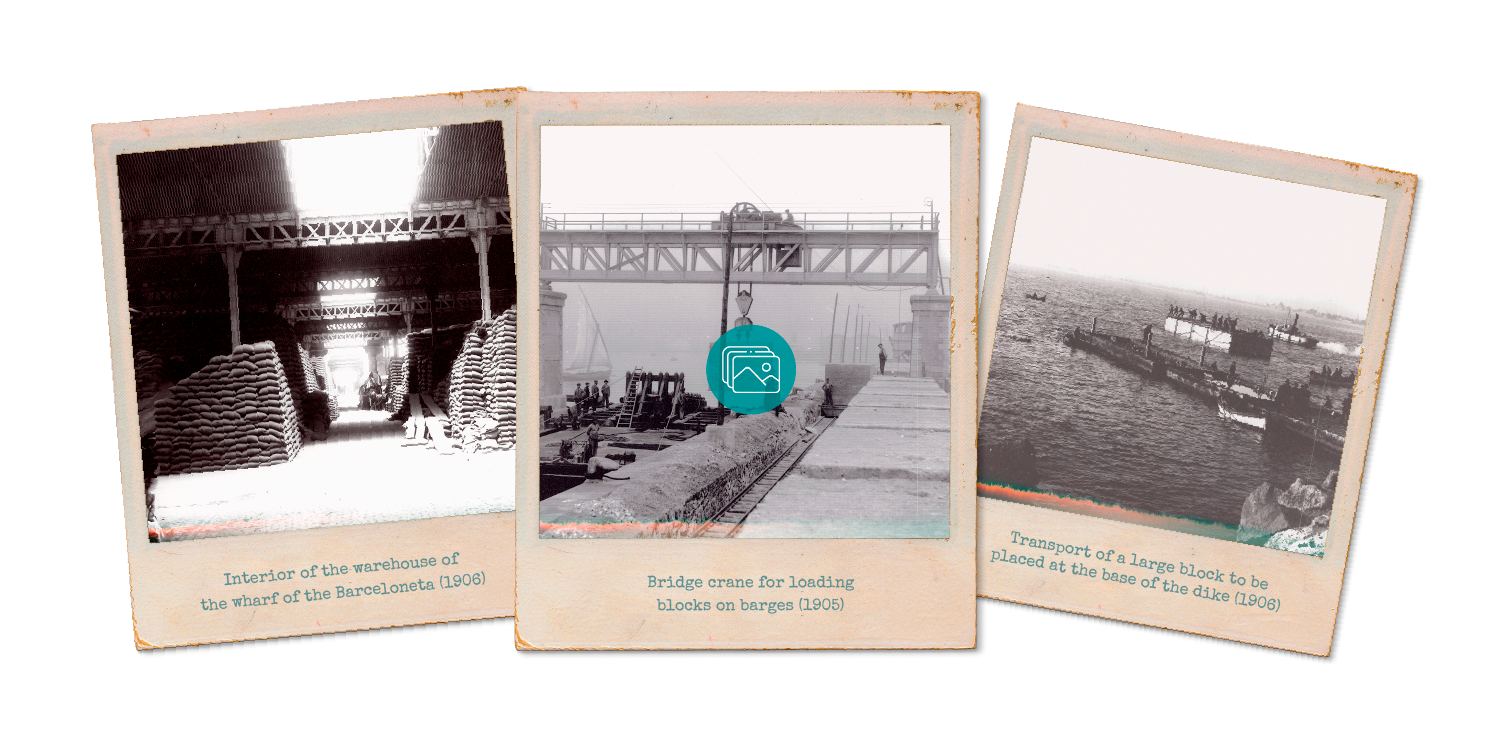

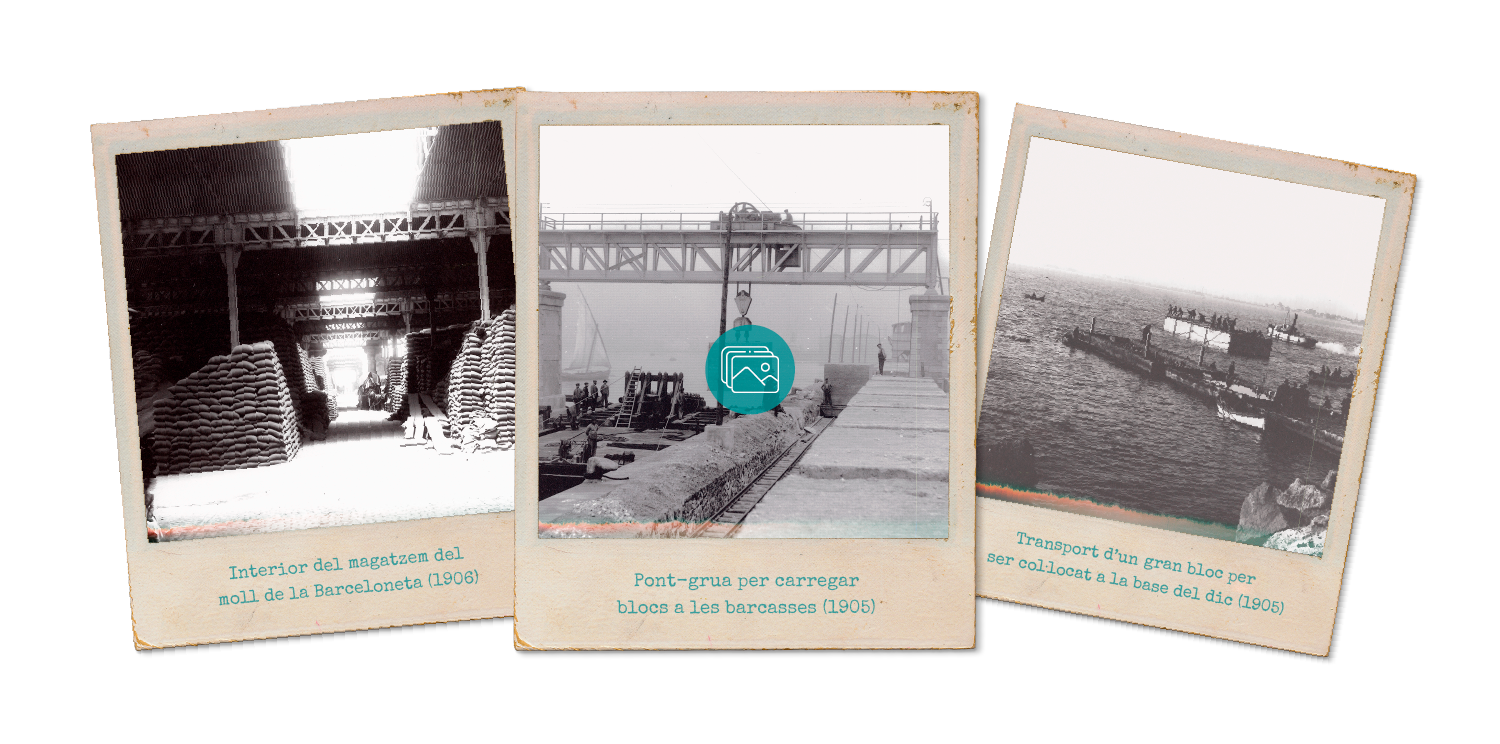

In August 2006, the building of a group of houses on the land of a former local railway station next to what is now the França railway station was accompanied by an intervention by the Archaeology Service of Barcelona. The remains of the port’s first breakwater (1477-1487) and the South bastion (1527), and the basement of the port's goods warehouse (1862) designed by the engineer Josep Rafo were discovered.

The first Port of Barcelona

The history of the first artificial port of Barcelona

Despite its maritime activity, the port of Barcelona did not actually acquire an artificial wharf until the mid-15th century. Thitherto, it had only had occasional wooden pontoon bridges used as makeshift jetties. In actual fact it did not need one because it already had a natural wharf, Les Tasques.

Rafaela Puig drew the first artificial wharf of the port of Barcelona in 1616. BNE

Les Tasques were long stretches of sand that ran parallel to the coast at a distance of about two hundred metres. They harboured a calm and navigable inner lagoon which would eventually hold a port area, all concentrated in what is now known as the Pla de Palau, where goods loading, unloading and trading activities were conducted and sailing vessels were repaired and built.

Taula de Canvi `{`Table of Change`}` - Europe’s first-ever public bank - founded in 1401, brought stability and prosperity, allowing the Council of One Hundred to transform the seafront into a space that symbolised municipal might. Thirty years afterwards, Alfonso the Magnanimous granted the licence needed to build an artificial port, which was paid for through a new tax, the so-called anchorage right. This came in response to the requirements posed by sea trade, which had reached an all-time high.

The decision was taken to consolidate a large part of Les Tasques with a wooden formwork packed with mortar and stone to be able to build a wharf on the eastern side of the city. An east-wind squall in the autumn of 1439 put paid to any progress. Building work was not resumed until 1446. Three pontoons - floating platforms - were assembled to transport stone to Montjuïc, where it was used to build the breakwater.

This initial phase brought the difficulties involved in the project to light. By blocking the flow of the sediments dragged in with the coastal drift, the breakwater gnawed away at the western beach and with it Les Tasques. The huge sandbar that had protected the beach of Barceloneta for centuries began to disappear.

In 1477, after the Catalan Civil War (1462-1472), the project was resumed in the middle of the seafront, following the outline that had been archaeologically documented. The work was overseen by the Sicilian master builder Stacio Alessandrino, who was eventually replaced by the municipal notary public Joan Maians. The project, completed in 1489, extended the breakwater out towards what was left of Les Tasques, which the sea had eroded into a cluster of islets. The island at the end of the wharf was named after the notary public of Barcelona: Maians’ island.

One century later, the Council of One Hundred extended that initial 240-metre-long and 15-metre-wide infrastructure with two 186-metre stretches. That medieval wharf provided the foundations for the modern port.

The continuity of a tradition

The book that recovers the thread of history

After a spell of economic stagnation that set in around the mid-16th century, the dynamism recovered at the beginning of the 18th century was nipped in the bud by the outbreak of the War of Spanish Succession and Catalonia’s ensuing defeat. Towards the end of the century, the enlightened historian, soldier, linguist, maritime economy scholar and politician Antoni de Capmany i Montpalau (Barcelona, 1742 - Cadiz, 1813) wrote his Memorias históricas sobre la marina, comercio y artes de la antigua ciudad de Barcelona [Historical Records on marine, trade and arts of the ancient city of Barcelona], which was published in Madrid in 1779. Capmany’s work heralded a seminal contribution to the economic history of Barcelona and helped to lay the foundations for the creation of the modern port in the second half of the 19th century. The topics that he analysed and recounted in this work are sea warfare and naval power, the merchant navy and trade, as well as the “useful arts” or production sectors of the city.

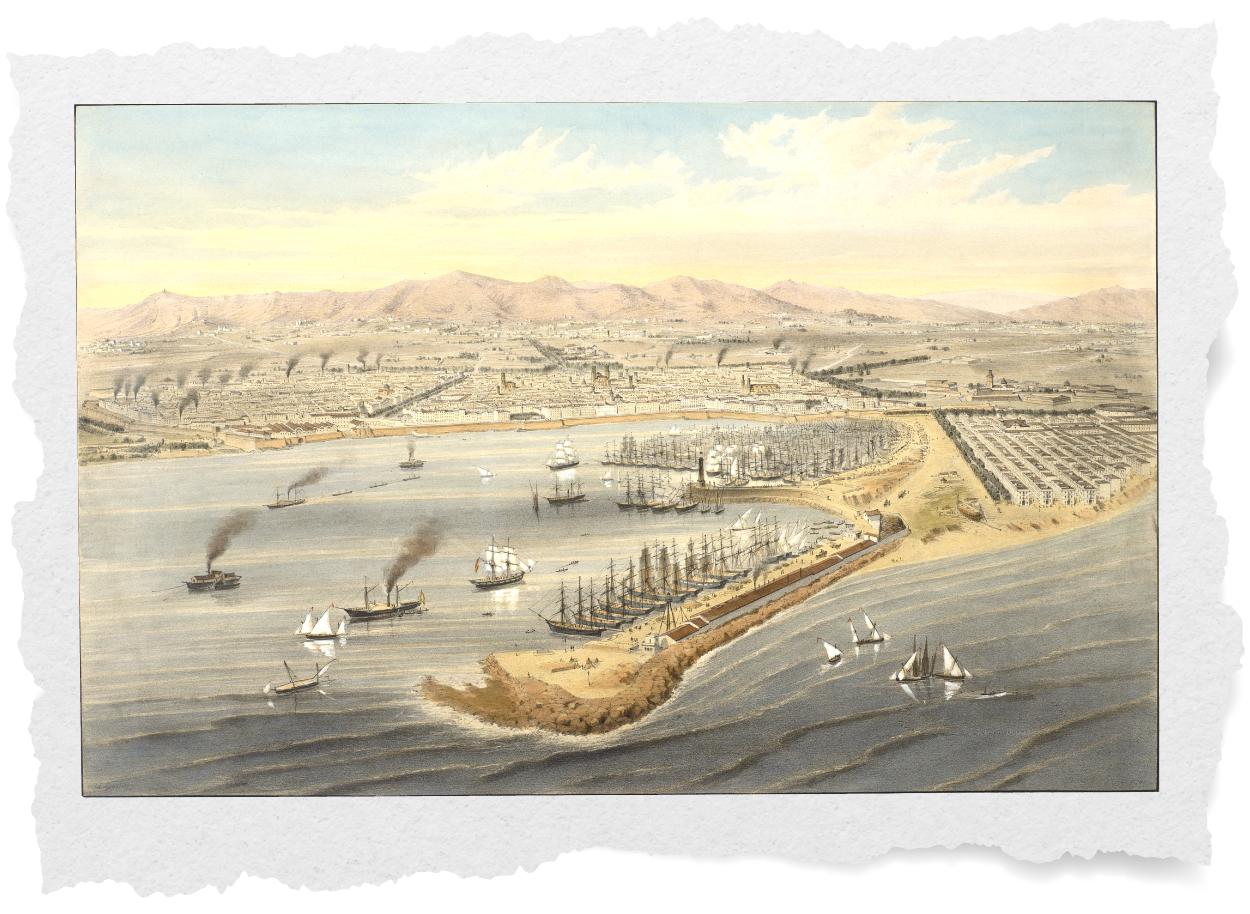

Lithography published in 1856 in the collection entitled L’Espagne a vol d’oiseau. The original dates from 1854 and was designed by Alfred Guesdon. AHCB

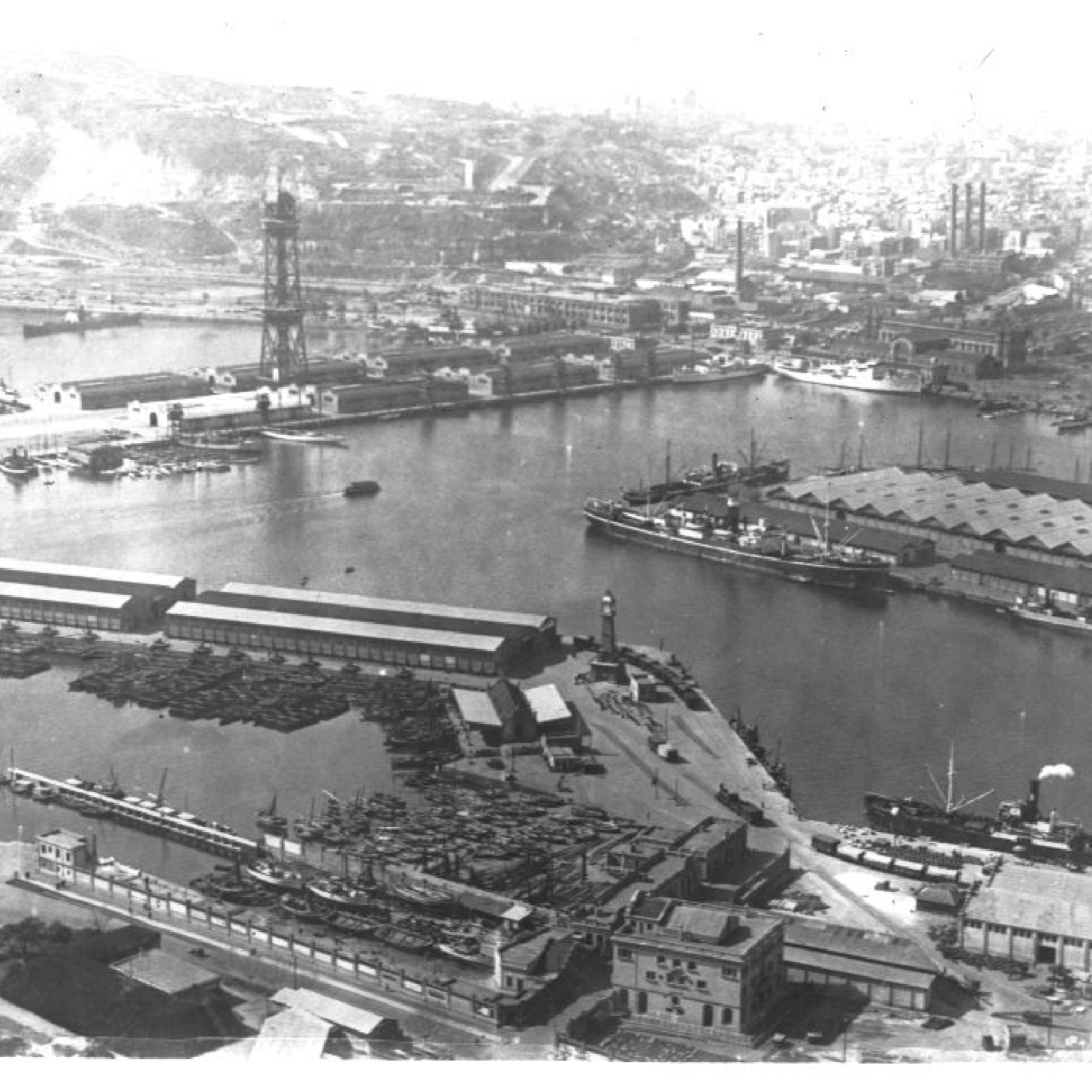

The port before the modern port

Illustrated by the Breton architect, draughtsman and lithographer Alfred Guesdon (1808-1876)

The images that best represent the port and seafront of Barcelona in the mid-19th century were produced by the Breton architect, draughtsman and lithographer Alfred Guesdon (1808-1876). The view here depicts the port in the foreground. The port’s infrastructure, facilities and activity are clearly visible. Despite the city’s ever-growing activity, the port was still a minor infrastructure work.

In the mid-19th century, during the rapid industrialisation of Barcelona and its immediate surrounds, the port evinced major shortcomings that hampered its economic development. The two main issues were a lack of protection and the shallow wharves and inner docks, caused by the influx of sand from the sediments dragged in by the seaboard dynamics.

- The New wharf, built between 1816 and 1822

- Lighthouse indicating the way into the port

- Talleres Nuevo Vulcano warehouses and factory

- The inner breakwater with the lighthouse from 1772

- The Old wharf, subsequently named the Barceloneta wharf

- Crane for hoisting heavy weights and fitting ship masts

- Goods on the wharf

- Small warehouses on the beach inside the port

- Small passenger jetty, built in 1849

- Steam-operated dredger

- Steamer towing three barges

- Two mizzen sail vessels

- Steamer unloading onto a barge

- Sailing ship being towed by two rowing boats

- Vessels moored by their prow in the new Wharf

- Vessels anchored off the Old wharf

- Adze master’s workshop

- Boats fishing

- Sea Gate

- Barceloneta

- Orchards of Sant Bertran

- Royal Shipyard

- Sea Wall

- Duc de Medinaceli square

- Santa Maria del Mar

- Rambles

- Steam-powered textile factories in the Raval district

- Church of el Pi

- Cathedral

- Royal Palace

- Passeig de Gràcia and Camps Elisis

- Ciutadella

- Barceloneta bullring

The expansion of the city towards the sea

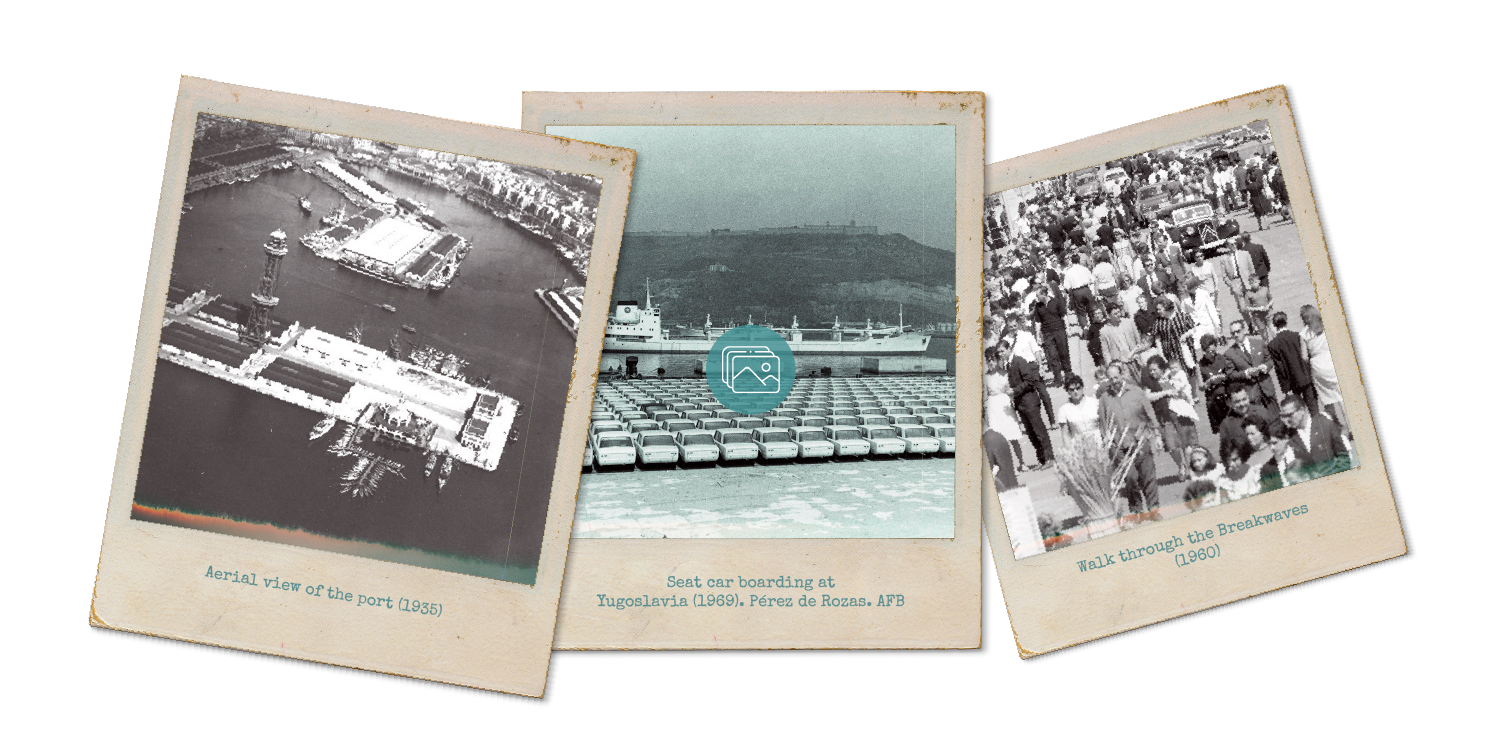

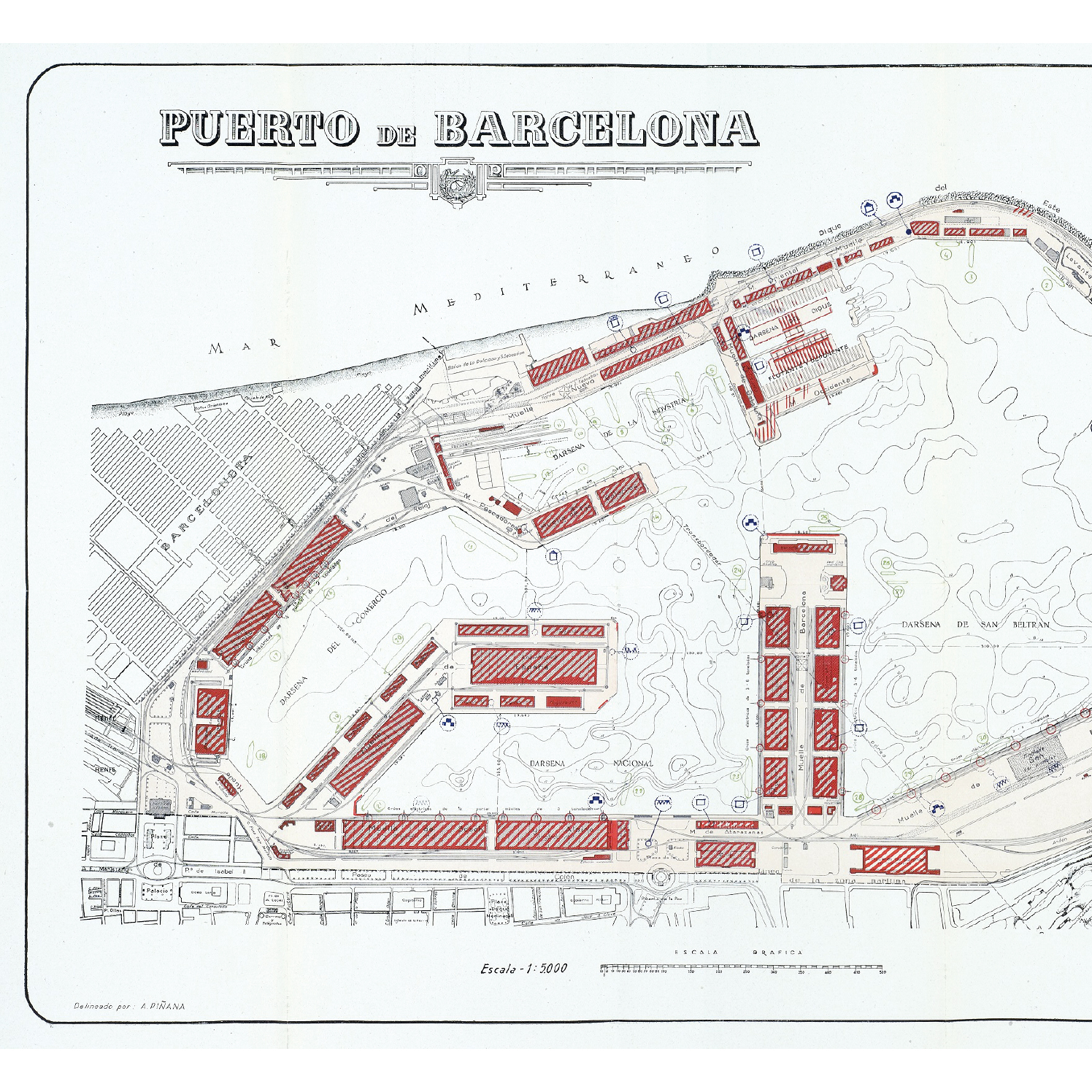

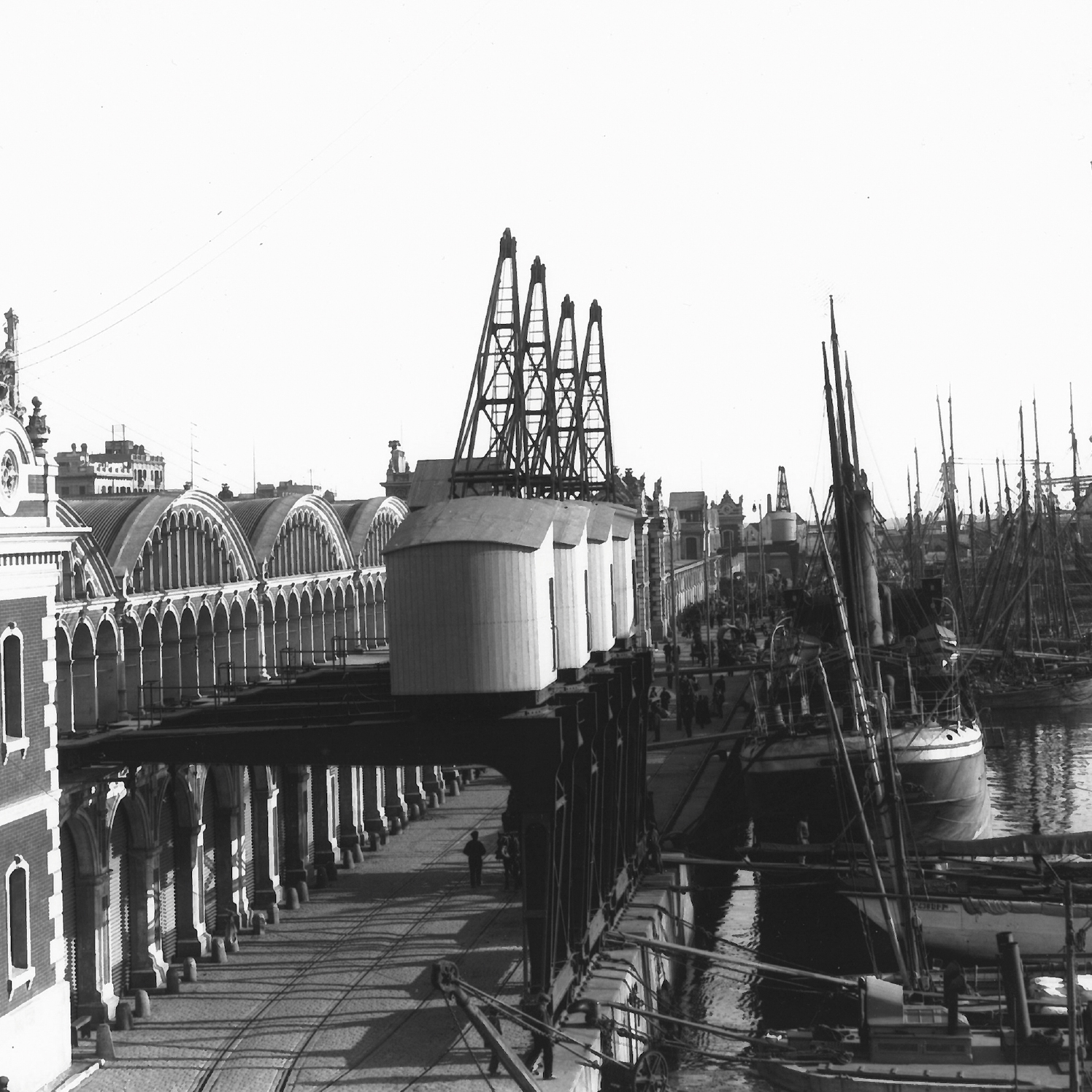

The port of Barcelona at the end of the 19th century

Ildefons Cerdà’s Reform and Expansion plan (1859). AHCB

The building of a modern and industrial port

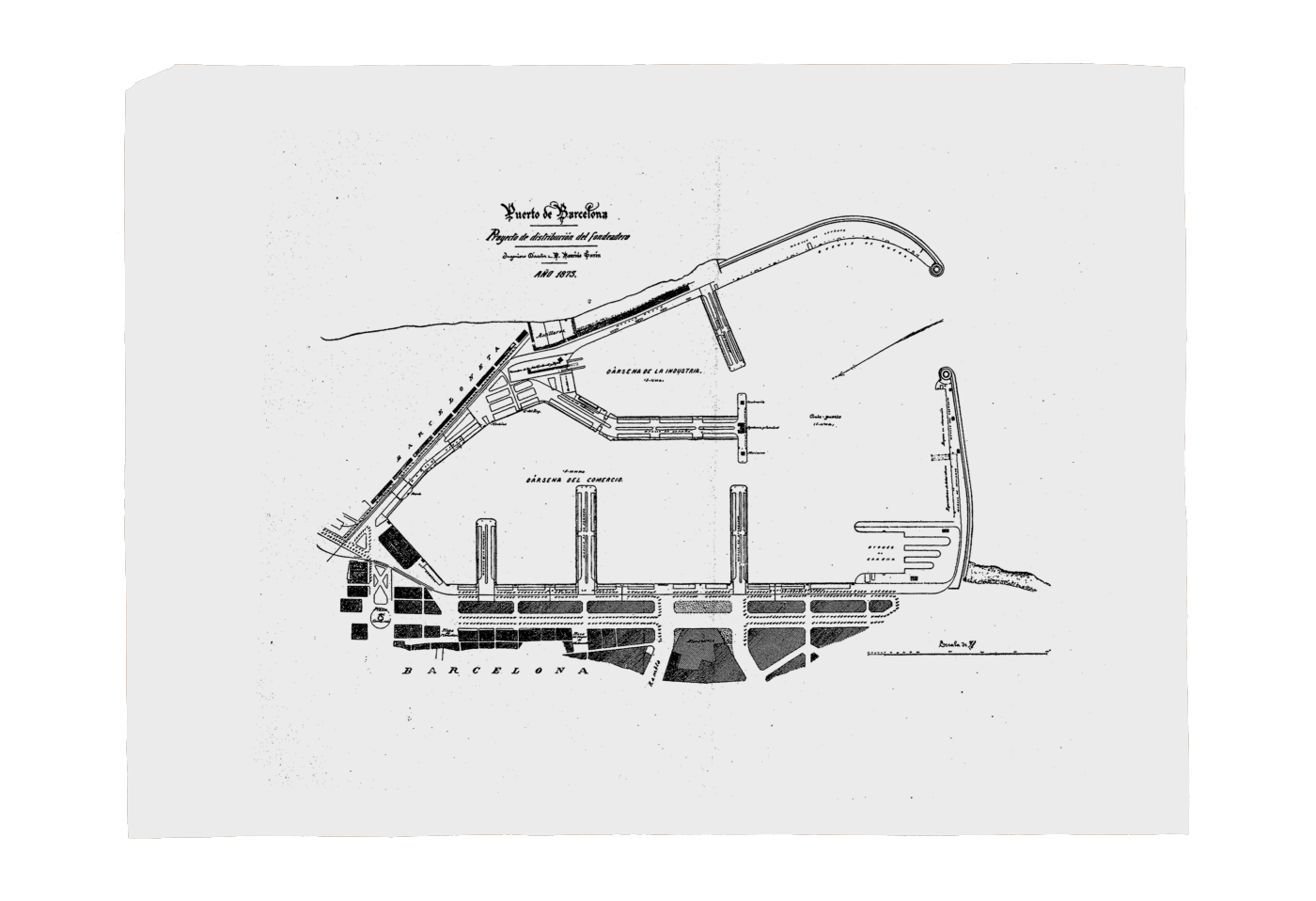

The plan to develop the city of Barcelona (1859) devised by the engineer Ildefons Cerdà, a pioneer of modern city development, already made provision for an industrial port designed by the engineer Josep Rafo and based on cutting-edge technical expertise of the time. When the walls were demolished, the new building initiative afforded the port a chance to grow. The year 1869 witnessed the constitution of the Board of Works of the Port of Barcelona, tasked with overseeing and managing the Port with a view to ultimately consolidating and increasing the port’s traffic and activity. Work on the industrial port based on the version of the project modified by the first director of the Board of Works, the Engineer Mauricio Garrán, was completed in 1875. Towards the end of the century, these improvements were rendered insufficient by the rapidly-growing sea trade.

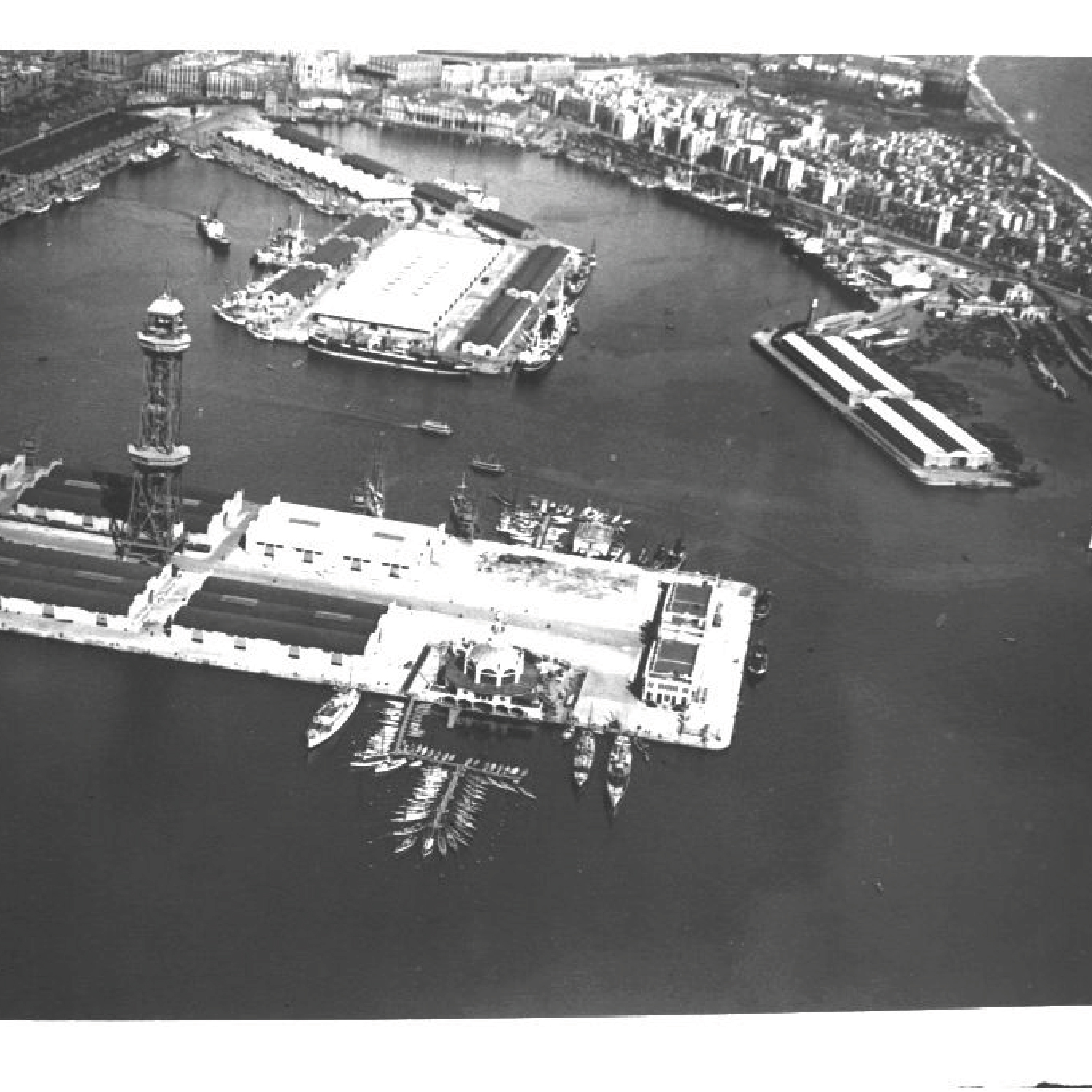

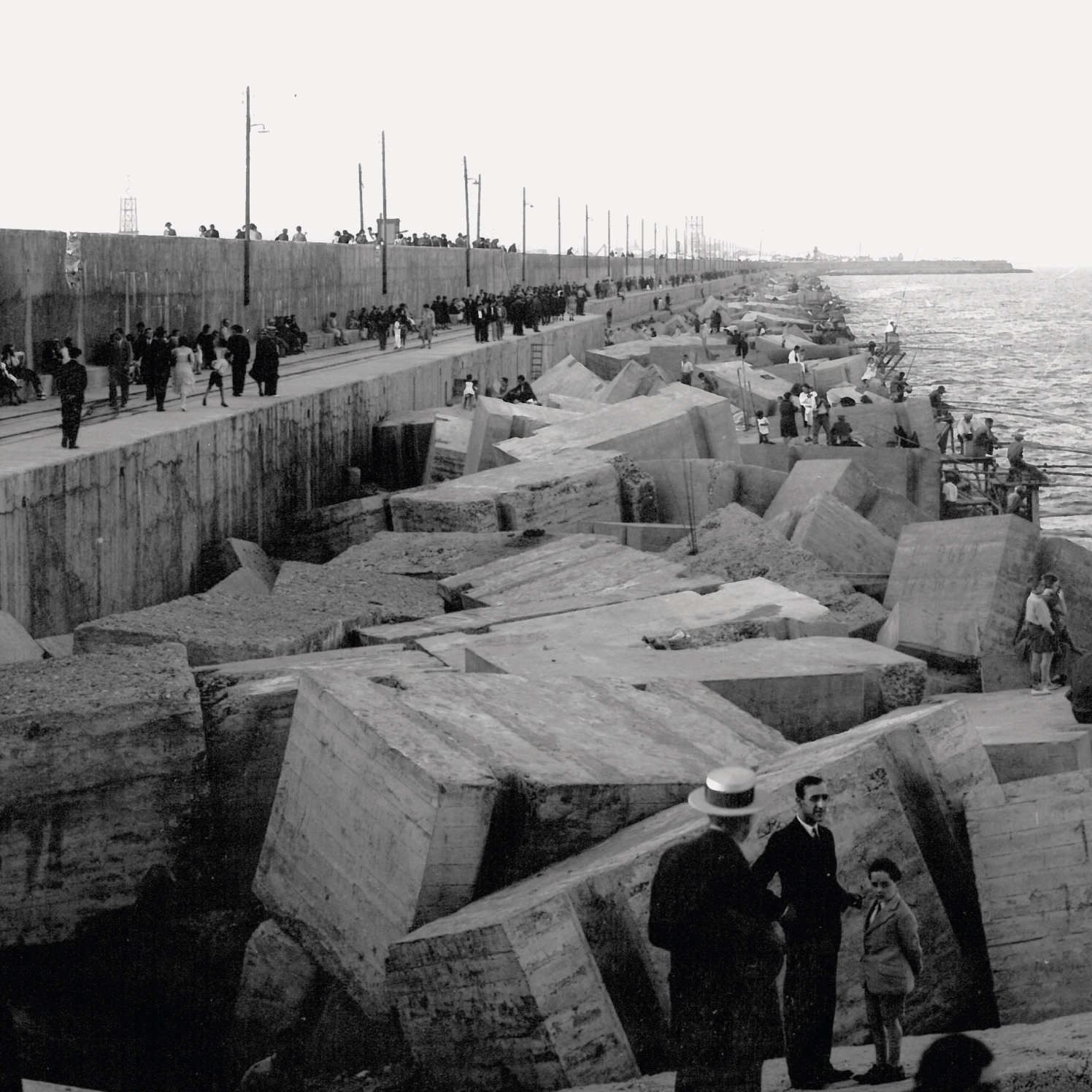

The port grows

One hundred years of expansion

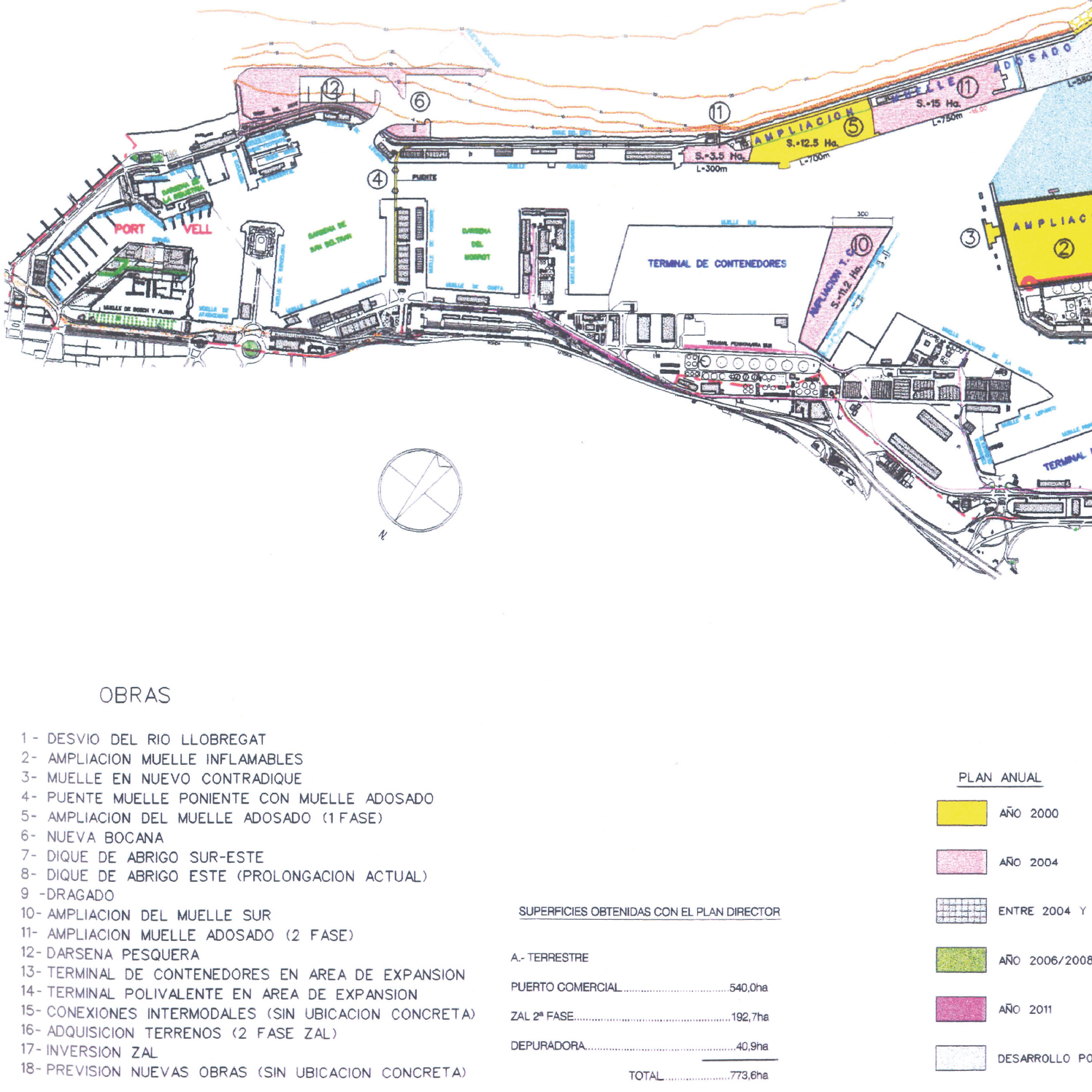

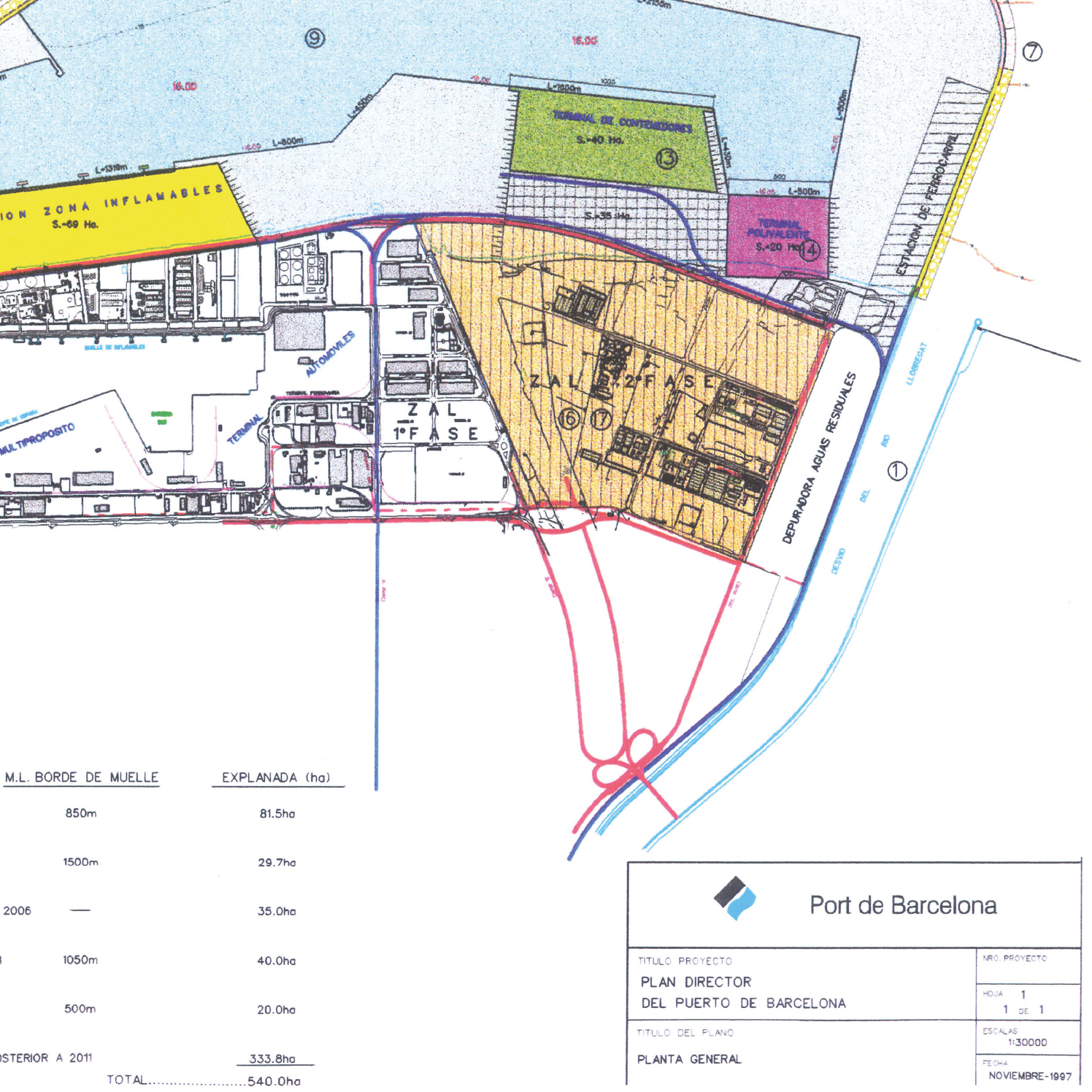

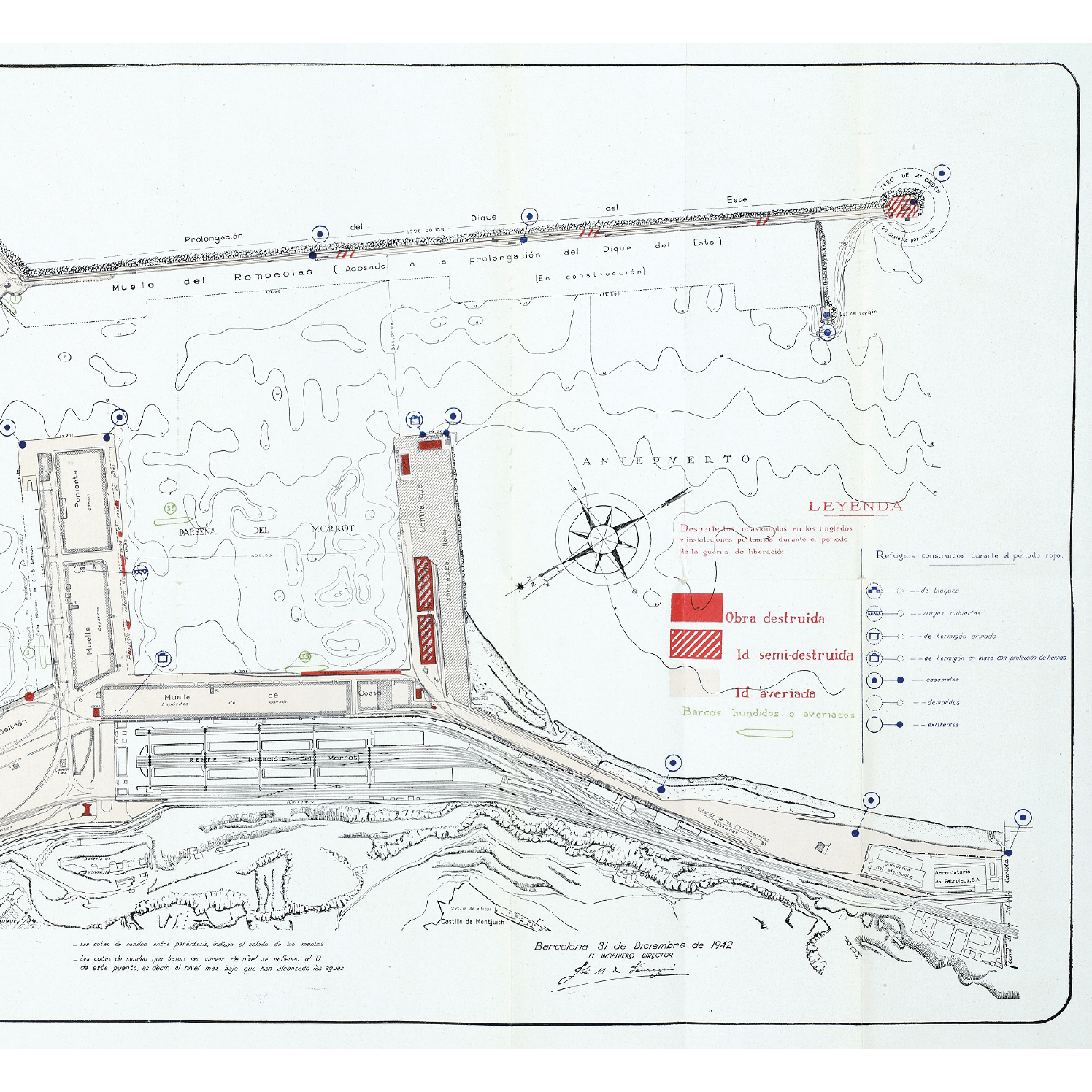

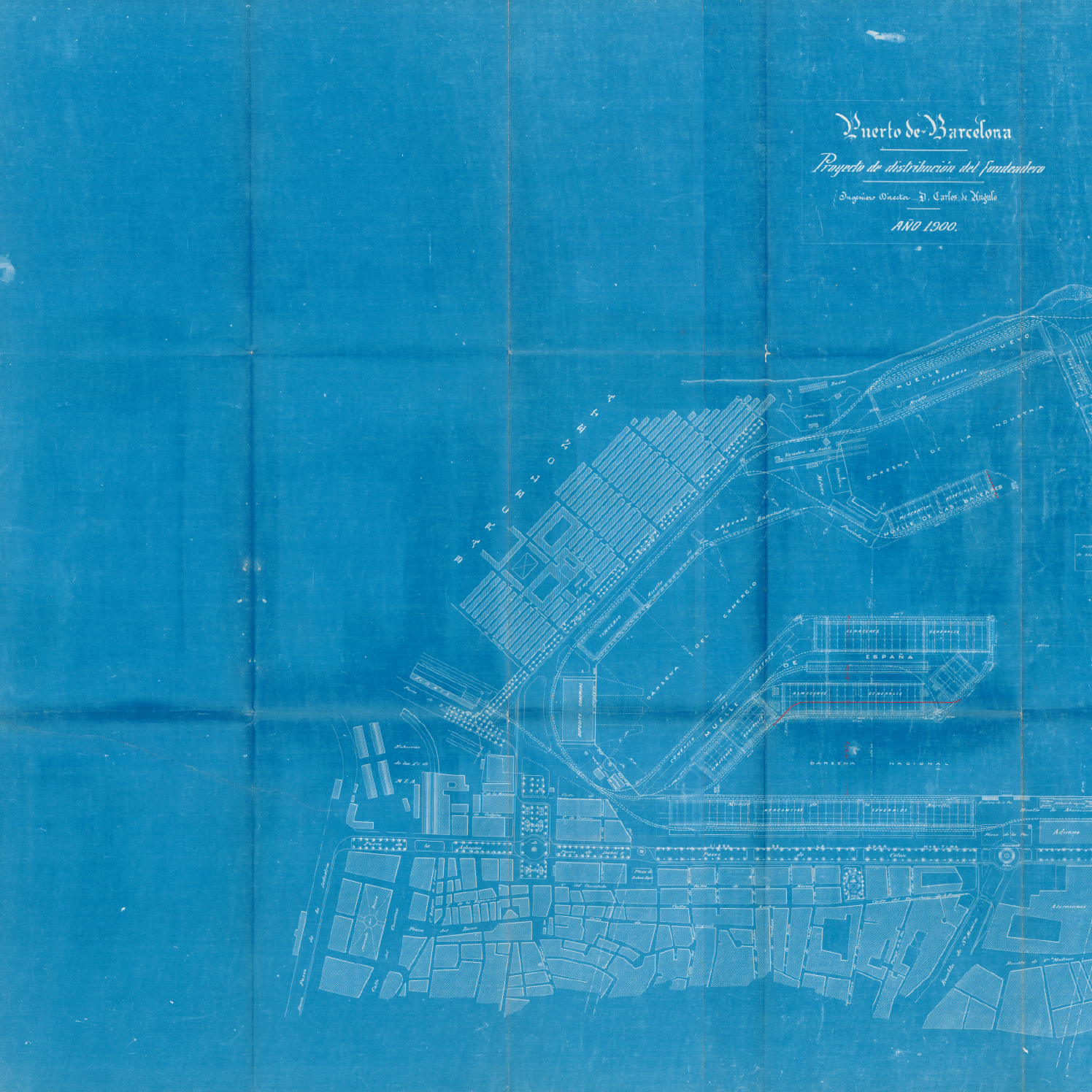

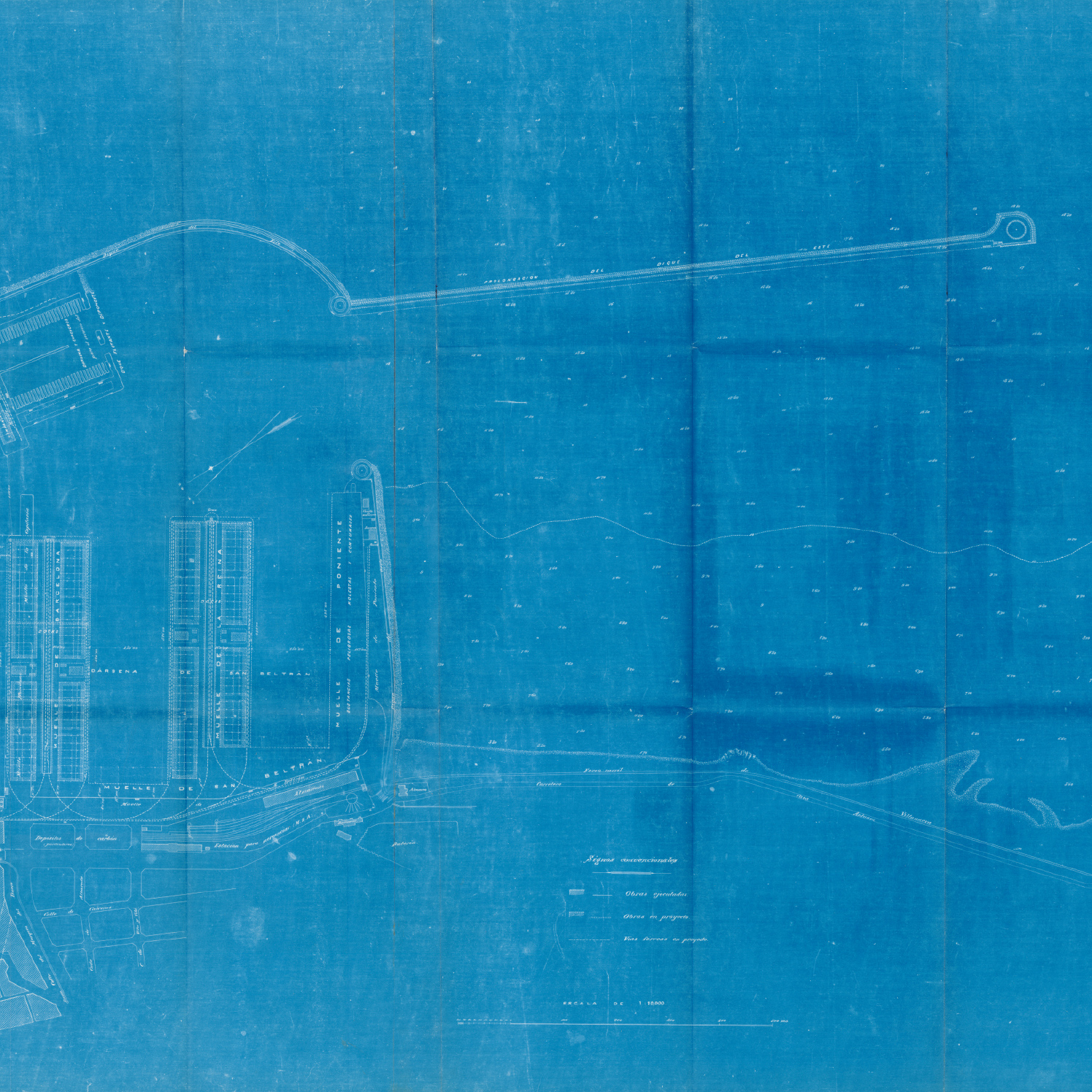

By the end of the 19th century, the port was in need of wider and deeper wharves, as well as better-equipped facilities for cargo loading and unloading. To this end, the chairman of the Board of Works, Carlos de Angulo, planned an expansion of the Port between 1900 and 1904. He defined an expansion of the East dyke and the building of a counter-dyke with sheltered water and wide, long and deep wharves that were fully equipped with warehouses and electric cranes. The work was completed in 1925. No further improvement or extension work was carried out on the port until 1965.

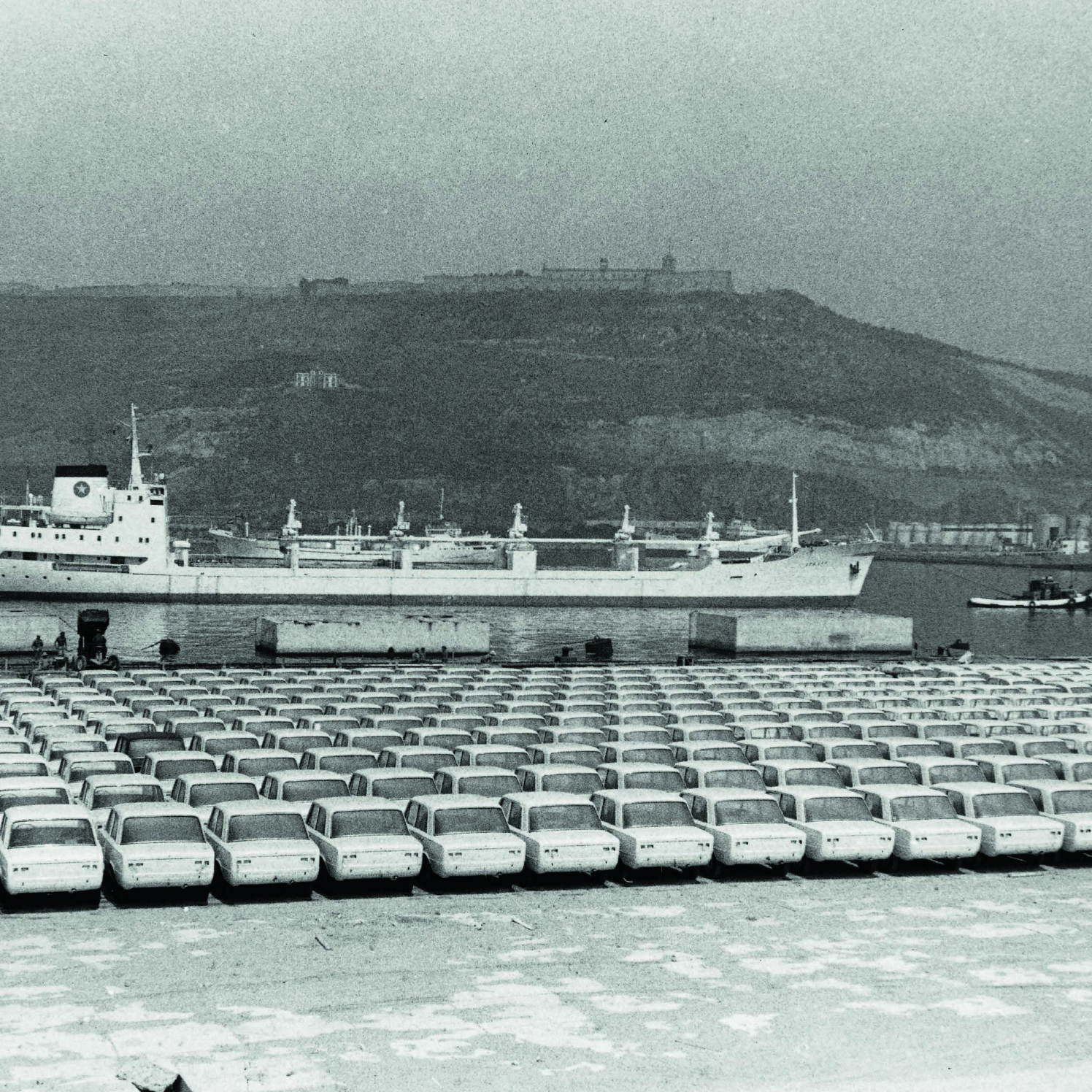

The air raids on the city during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and Franco’s ensuing autarky impacted the port’s infrastructure and traffic. The economic policy of the dictatorship did not change until the 1960s. At that time, coal, thitherto the main trading commodity, made way for cement, petroleum by-products and natural gas. Containers also appeared on the scene. In 1965, the port was extended towards the foot of the Morrot de Montjuïc and south towards the river Llobregat. This work, which lasted until 1980, ultimately yielded a container terminal, an inflammable products wharf, an automotive terminal, an overland haulage hub and specialised installations.

As of the 1980s, the port was managed as the Autonomous Port of Barcelona. With the support of private initiative, it executed three ground-breaking projects: the first one was the special plan for the Old Port (1989), which opened up the area near the city to the general public; the second project was the development of cruise ship traffic stemming from the Olympic Games (1992); the third project was the creation of the Logistical Activities Zone, ZAL (1990), a major hub for goods reception, distribution and activities. Subsequently, a new master plan (1998) extended the port, doubling its operating surface area between 2001 and 2011. As a result of this extension, goods traffic rose from 24.7 to 67.7 million tonnes in a matter of twenty years, between 1998 and 2018.

Port time-line

From past to present

Ever since the Board of Works was created, the port has grown by dint of four major projects and the corresponding work.

Mercè Conesa

President of the Port of Barcelona

(Portal de la Pau, 4 March, 2021)

José Alberto Carbonell

Director General of the Port of Barcelona

(Portal de la Pau, 4 March, 2021)

- The logistic port is the area destined to the development of logistics services linked to port activity. It is an internodal center that offers different services through the rental of ships.

- The energy port is the area for petroleum by-products, gas and chemical products. It plays a key role in the receipt, storage and distribution of the energy resources of an extensive territory.

It has a key role in the reception, storage and distribution of the energy resources of a large territory. - The comercial port is used for loading and unloading goods. It boasts specialised multi-purpose terminals and facilities for cabotage with the Balearic Islands and other nearby ports.

- The port of the passes is the area for ferries and cruise ships. It has specialized maritime terminals depending on the transit.

- The Annport is the urban port, open and to citizens and recognized throughout the world as a paradigm of integration between port and city.

With 70 hectares, it concentrates port and fishing activity and nautical and sports services, culture and training, business, commerce and leisure. - Between the Portal de Mar and the old ferry of Migjorn, today next to the station of France, is where in 2008 the remains of the first artificial port of Barcelona, built from 1477 and that became the initial base of reforms to the port of today.

Next to the mediaval breakwater, appeared the wreck Barceloneta I.

Historic Map of Barcelona

The cartographic evolution of the seaboard, seafront and port of Barcelona

Epilogue

The Port and the city

The Historic Map of Barcelona depicts the evolution of the city and its seaboard by dint of the brisk trade and port activity which, halfway through the 15th century, culminated in the creation of Barcelona’s first wharf. Since then, the port has been a key infrastructure and an economic mainstay of Barcelona and Catalonia.

The Barceloneta I attests to and recalls that thriving medieval sea trade. The first wharf originally paved the way for the modern port, the core of the reforms implemented towards the end of the 18th century and, 150 years later, the modern port. A 21st-century port that links us to the world, as it also did more than 600 years ago.

Credits and acknowledgements

The Port of Barcelona is committed to the heritage and the history of Barcelona and Catalonia and to preserving and disseminating them.

This exhibition was held jointly with the Museum of History of Barcelona.

Special thanks to Antoni Gelonch, president of the Cercle del Museu d’Història de Barcelona (Casa Padellàs, March 10, 2021) See video

Documentary sources

El Port de Barcelona. De la creació de la Junta d’Obres a l’actualitat 1869-2019, by Joan Alemany. Autoritat Portuària de Barcelona, 2019.

Barcelona, Mediterranean Capital - The Medieval Metamorphosis, 13th-15th Centuries.Room booklet no. 30. MUHBA, 2019.

Barcelona, a Mediterranean port between oceans. The testimony of the Barceloneta I ship. Room booklet no. 33. MUHBA, 2021.

Graphics and multimedia

Archive of the Port Authority of Barcelona (APB)

Photographic Archive of Barcelona (AFB)

Historic Archive of the City of Barcelona (AHCB)

Filmoteca de Catalunya (FC)

Image from the collection of the National Library of Spain (BNE)

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek (ÖNB)

Archaeology Service of Barcelona (SAB)

Historic Map of Barcelona. Cartographic document. MUHBA.

Boat model: Marcel Pujol, Lluís Rovira i Bruno Parès

Design of the Consulate of the Sea map: Andrea Manenti

Contribution of content and advice

Team of the Museum of History of Barcelona (MUHBA), Mikel Soberón, Aina Mercader and Joan Alemany

Script

Quaderna, Estratègia Corporativa

Audiovisual and interactive

Tururut, Art Infogràfic and Paula Ustarroz

Proofreading and translations

Gemma Garcia Reverte and Allan Bebbington

Production and communication

Produccions Planetàries Solucions Audiovisuals

Production

Port Authority of Barcelona Department of Cultural Heritage,

Barcelona, May 2021